Seldom, I suspect, has an Australian novel met with the rapturous critical acclaim showered on Autumn Laing, Alex Miller’s latest and seemingly greatest offering. When it appeared late last year there were accolades aplenty: ‘a novel of bravura intensity and insight,’ …. ‘inhabited by characters whose reality challenges our own.’ …. ‘a novel in which facts are forever being bent to the service of ideas,’ …. ‘a triumphant appropriation of vulgar if high-toned gossip for the purposes of unrepentant art.’ …. ‘rare and radiant fiction. An indispensable novel.’

The applause is well deserved.

Miller has borrowed a handful of the key characters from what is probably the best known cultural saga in Australia, and rendered them truly his own. All who are even remotely familiar with the ménage at Heide during World War 2 and beyond will immediately make connections and morph Heide into Old Farm, Sunday Reed into Autumn Laing, her husband John into Arthur, and her painter lover Sidney Nolan into Patrick Donlon; Nolan’s first wife Elizabeth Patterson is clearly Edith Black; less obvious is the Barrett Reid/Barnaby Green pairing and greater familiarity with the real people is necessary to make this connection before reading Miller’s revealing post script ‘How I came to write Autumn Laing’.

These are the main characters of the novel and they emerge very much as being of Miller’s making, but as might be expected, there are some coincidings of the real and the imaginary. A major series of paintings, Nolan’s Kellys and Donlon’s Hinterland, each themed on a national icon and destined to change the direction of art in this country, is one; the breakdown in the relationships between Pat and Autumn and between Sid and Sunday is another. Some few others coincide in the most minute detail – Arthur is reading Wilenski’s The Modern Movement in Art when Pat comes to his office, as was John Reed when Nolan came to his. I am sure the cognoscenti have enjoyed looking for pairings less obvious, and testing their knowledge with teasers such as is there a real life Adeli Heartstone and could the legendary Basil Burdett really have been at all like the rubbishing Guy Cowper?

However ruminations like these will only serve to diminish for the reader Miller’s great achievement in taking the bare bones of history and giving them, per medium of his keen insight and compelling prose, new flesh to be clothed in his literary finery.

In the acknowledgements Miller states that Autumn is ‘my own fictional character, but if her imaginary life touches from time to time on real historical themes’ his inspiration was to be found in Janine Burke’s The Heart Garden: Sunday Reed and Heide (Knopf, 2004). The characters are certainly his own, but to the extent that fact and fiction do inevitably blur, I find Sunday Laing and Pat Donlon to be painted more through Barrie Reid-tinted glasses. Miller first met Reid six years before he died and regarded him as a dear friend – indeed there is an almost domino-like effect in the infatuation of Nolan and Sunday Reed, the infatuation of Barrie Reid with both, and the apparent infatuation of Miller with all three.

Reid died in August 1995 exactly a month before the anthology of his poetry, Making Country (Angus & Robertson, 1995), was launched at Heide by Miller with readings by Shelton Lea. Just days before his death Reid was given a prepublication mockup of the book, and on this mockup he made personal comments and notes.1 Against the poem “The Artist” Reid has written: ‘Nolan of course.’ “The Artist” includes the lines: Now night comes, now your slow / eye learns new tricks. Old / tricksters feel the cold, / move fast. Don’t look now / Herr Dr Conjurer. The influence of Barrie Reid, more so than Janine Burke, inflects passages such as Autumn’s observation early in the book: ‘Pat was never deep. He was intuitive, but he was not deep. It was I who was deep.’

Miller’s characters, especially Autumn, pulsate with life and I suspect few men have ever so believably written as an ageing woman. In their recent book Sunday’s Garden: Growing Heide (Miegunyah Press, 2012), Kendrah Morgan and Lesley Harding describe Sunday as ‘elusive, paradoxical and endlessly fascinating’ – surely as succinct an encapsulation of her character as has been written. What I find endlessly fascinating about Autumn Laing, is that without being Sunday Reed, she is also elusive, paradoxical and endlessly fascinating.

So too is this book, which opens brilliantly on New Year’s Day 1991 with Autumn’s staccato utterance ‘THEY ARE ALL DEAD. AND I AM OLD AND SKELETON-GAUNT. THIS is where it all began fifty-three years ago.’ Quite remarkable is that just four months later in real time, at the very end of one of his last interviews, Nolan used virtually the same phrase when summing up his years at that old farm: ‘Well, they’re all dead,’ he says, ‘including the dog…. such a curious feeling isn’t it?’2

Miller speaks in his post script of the ‘private shallow grounds of contradiction and elaboration beyond fact and outward appearance that interest me. Fiction is the only mode with which we can approach this ground in others. …. we are at liberty to do it well’ – and it is done exceedingly well here – ‘in which case our readers are convinced and willingly enter the illusion with us.’ This brings to mind Nolan’s comment ‘Painting is I suppose meant to be a way of getting rid of lies’ – not quite the same as the aphorism attributed to Picasso, ‘art is a lie that shows us the truth,’ nor the Nabokov line used by Miller as his fore-quote: ‘The most enchanting things in nature and art are based on deception.’

Illusion and deception however, like beauty, are in the eyes of the beholder, and in Autumn Laing we have only Autumn’s perspective. How great if this were but the first book in a Miller tetralogy wherein, as in Talking to a Stranger,3 differing illusions and deceptions appear when seen from the perspectives of each of the main players. Indeed there is a congruence with Spring Snow, the first in Mishima’s Sea of Fertility tetralogy, with both books sharing a seasonal title.

What a challenge! Autumn Laing – telling of art, love, creativity and redemption; Patrick Donlon – telling of art, love, creativity and …. (perhaps) betrayal; Arthur Laing – telling of art, love, creativity and …. (perhaps) disappointment; and Barnaby Green – telling of art, love, thwarted creativity, and …. (perhaps) delusion. Their lives intertwining kaleidoscopically, the ashes of three of them mingling in real life death at the foot of the huge tree at Heide from which aborigines once took bark for their canoe, the other resting in London’s Highgate Cemetery where his gravestone proclaims him PAINTER – one whose alchemy was forged in the crucible of an old farm and who, perhaps more than any other painter, brought to the world the essence of this ancient land.

A biography of Nolan is nearing completion, one on the Reeds is in planning, and one on Barrett Reid – who in my view will be shown in time to have underpinned much in the lives and relationships of the other three – will surely appear one day. With these publications, fact could well be shown to be not only stranger than fiction, but, like both Sunday and Autumn, more elusive, more paradoxical and more endlessly fascinating. Meantime, we are fortunate that Alex Miller – whose expatriation from England to Australia is somewhat a mirror reversal of Nolan’s – has given us Autumn Laing.

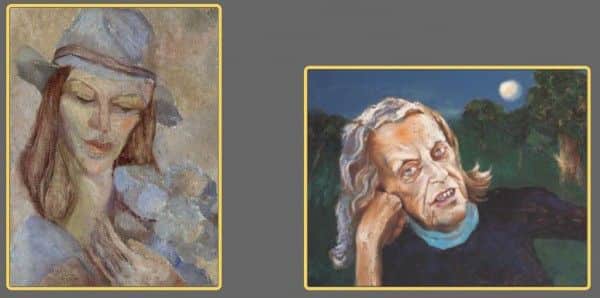

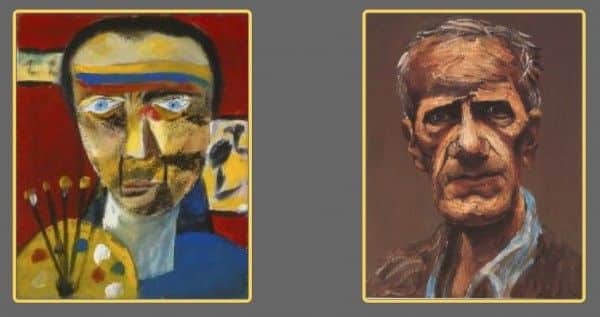

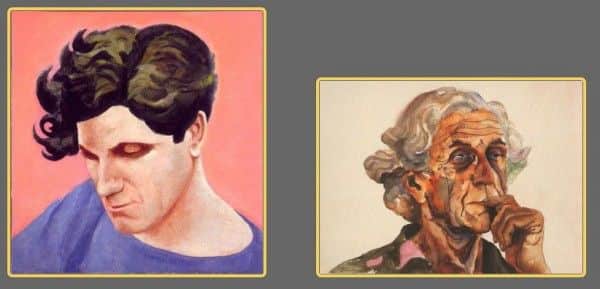

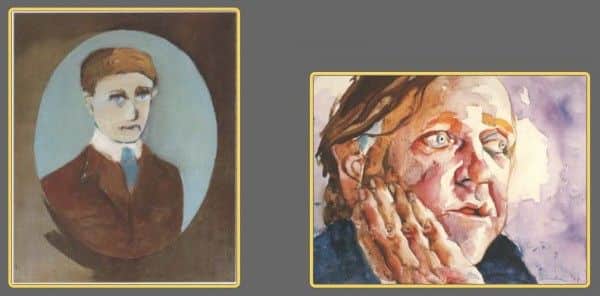

A novel spanning fifty plus years must inevitably touch on ageing, so here by way of conclusion are images bridging the period, the later ones fleshed out from the perspective of artist Albert Tucker, their contemporary for all those years.

Sunday Reed: (1) by Moya Dyring, 1934, Heide Museum of Modern Art; (2) by Albert Tucker, 1985, private collection

Sidney Nolan: (1) self portrait, 1943, Art Gallery of New South Wales; (2) by Albert Tucker, 1977, private collection

John Reed: (1) by Adrian Lawlor, c. 1938, Heide Museum of Modern Art; (2) by Albert Tucker, 1982, private collection

Barrett (Barrie) Reid: (1) by Sidney Nolan, 1947, Queensland Art Gallery; (2) by Albert Tucker, 1983, private collection

These Tucker portraits come from his 1985 Tolarno Gallery exhibition Faces I have met, of which he wrote ‘I wanted to deal with past history, a 40 year episode really. These are the portraits of the survivors and the participants over that time’.4 The exhibition title comes from Eliot’s “Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock”: There will be a time, there will be a time / To prepare a face to meet the faces that you meet; / There will be a time to murder and create.5

Surely such images host more than one excursion of the imagination!

Finally, here are links to some reviews of Autumn Laing appearing around the time of publication:

http://www.geordiewilliamson.com/2011/10/01/alex-miller-autumn-laing/

http://www.australianbookreview.com.au/files/Features/October_2011/Fraser_review_ABR_Oct_11.pdf

http://www.themonthly.com.au/autumn-laing-alex-miller-janine-burke-3970

http://www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/bookshow/review-autumn-laing-by-alex-miller/3593940

ENDNOTES

- Photocopy of the mock-up, a gift from Shelton Lea, in possession of the author.

- Sidney Nolan, interviewed by Michael Heyward, 5 April 1991, Papers of Michael Heyward, Australian Manuscripts Collection, State Library of Victoria, PA 96/159, Box 5.

- Talking to a Stranger is a powerful four part BBC television drama produced in 1966. Written by John Hopkins, it recounts the events of one weekend from the viewpoints of four members of the one family.

- Albert Tucker, Faces I have met, Tolarno Galleries, Melbourne, 1985.

- The Tucker portraits are eloquently discussed by Michael Keon, another contemporary of all parties, in his Glad Morning Again, Imprint, Sydney, 1996, p. 304.