Abstract:

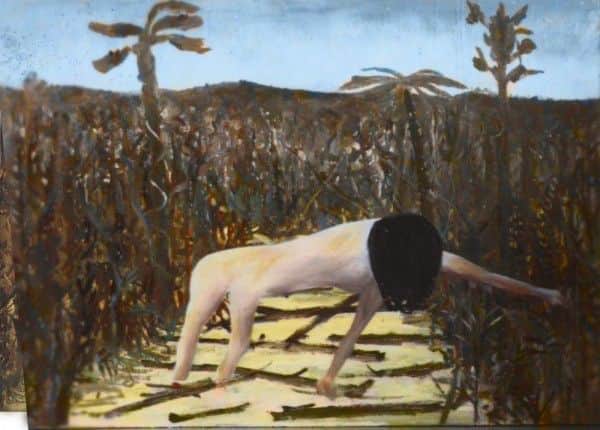

Sidney Nolan’s painting Mrs Fraser has long been regarded as emblematic of his animosity towards Sunday Reed. Painted on Fraser Island only months after he left Heide never to return, the work has inflamed viewers for more than 60 years. Nolan’s time at Heide and Eliza Fraser’s rescue from ‘savages’ a century earlier are so well known as to demand little retelling. Nolan lived in a ménage à trois at Heide with Sunday and John Reed and departed in 1947 to discover the legendary tale of Eliza’s rescue and her alleged betrayal of Bracefell, her convict rescuer. Over the next 40 years Nolan conflated that story with his own, seeing himself as the betrayed Bracefell and Sunday as the betraying Eliza. From Fraser Island Nolan sent the Reeds photographs of some of his paintings , and these hitherto unreported images include one of an earlier version of Mrs Fraser. Reconstruction of the original encourages a deconstruction of the belief of many commentators that Nolan painted this first iconic Mrs Fraser to denigrate Sunday Reed. His animosity was to come later.

Background

The following outline will assist those unfamiliar with the threads binding Nolan to Sunday Reed and Eliza Fraser.

On 22 May 1836 the brig Stirling Castle ran aground on Swain Reef off the central Queensland coast. The crew and Captain Fraser’s wife Eliza abandoned ship and sailed south in the ship’s pinnace and longboat, and six weeks later the longboat landed at Orchid Beach on the northern tip of what is now Fraser Island. Setting off along the beach, Eliza, her husband, and ten crew members met up with groups of aborigines and bartered their way south until their equipment and clothing were exhausted. Naked, they were forced to shoulder the workload of their aboriginal hosts. After several weeks they reached the mainland at the southern tip of the island and by then five of them, including Captain Fraser, had perished. Those remaining would all survive, Eliza being rescued dramatically from the midst of hundreds of aborigines at a corroboree and taken to Moreton Bay. Legend has the escaped convict David Bracefell as her rescuer. Bracefell lived with mainland aborigines and told a tale of single-handedly rescuing Mrs Fraser, and hoping for pardon, leading her from her captors through swamps and bush towards Moreton Bay only to be betrayed by her as they neared the settlement. This became the narrative of legend and soon displaced the contemporary historical account in which the convict John Graham rescues Eliza. Exactly what happened in the days before Eliza’s rescue will probably never be known, and whether David Bracewell – not ‘Bracefell’ or ‘Bracefield’ as some records have him – played any part at all in the rescue is uncertain. If Bracewell was involved, and close analysis suggests he was, he and Eliza may have had a sexual encounter leading her to say she would speak against him. This intrigue has served well in keeping the story alive for nearly two centuries. A more fullsome account of Eliza’s trials and rescue is in the article Eliza’s Landfall.

A century later John and Sunday Reed purchased an old farmhouse and land at Heidelberg outside Melbourne, and Heide, as their affectionately abbreviated retreat became known, is now the Heide Museum of Modern Art. Sunday was born in 1905 into Melbourne’s prominent and prosperous Baillieu family, and with her husband John, the Cambridge-educated lawyer son of a wealthy Tasmanian pastoralist, had wealth allowing them to indulge their passion for modernism. Heide was home and haven to a procession of avant-garde artists, and the Reeds not only bought their works, but mentored and financially supported them.

Sidney Nolan is the artist most associated with Heide. He was born in Melbourne in 1917 and lived in bayside St Kilda where, as the son of a tram driver, his education was basic. At age 14 he left school to commence a design and craft course and then worked with a firm of hat makers for six years. In 1934 he commenced art school night classes at the National Gallery of Victoria and four years later his search for a measure of financial security brought him into contact with the Reeds not long before he married Elizabeth Paterson, one of his fellow students at the Gallery Art School. Nolan was just 21 and his meeting with the older couple would redirect his life. He spent more and more time at Heide and he and Sunday became lovers. Soon after the Nolans’ daughter was born early in 1941, Elizabeth told Nolan that the marriage was finished and when she refused to relent, in due course he moved in at Heide.1 The ménage was interrupted by war service when Nolan enlisted in March 1942 and was posted to the Wimmera, where his proximity to Heide allowed for frequent weekend visits. He went AWL and was declared an illegal absentee in September 1944.2 For the next few years he took the false name Robin Murray and lived in hiding at Heide and in a converted stable at Parkville known as ‘The Loft’. In 1946 the Reeds holidayed in Queensland where they met Barrett (Barrie) Reid who was editor of the Brisbane little magazine Barjai. At their invitation he visited Melbourne for Christmas, stayed at Heide and at ‘The Loft’, and established a strong rapport with Nolan who was then in full swing painting the first iconic Kelly series. Poetry written by Nolan at the time indicates that he and Reid discussed his situation at Heide, and Reid suggested to Nolan that he come north for a period.3 Finally, amid much inner turmoil,4 Nolan decided to move on. His time at Heide had come to an end and he flew to Brisbane in July 1947 a few months after his 30th birthday. A more detailed account of this period in their lives appears in the essay Threads.

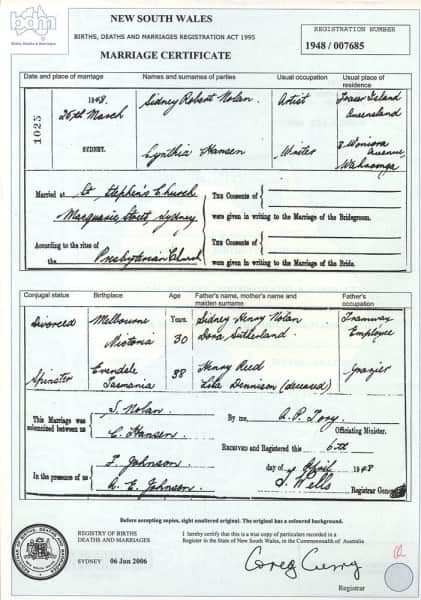

Nolan stayed in Queensland for the remainder of 1947 and used Barrie Reid’s family home in suburban Chermside as a base. His travels throughout the state during this period were extensive – he visited not only Fraser Island but travelled as far north as Cooktown, west to the Carnavon Ranges and to Mt Tamborine in what is now the Gold Coast hinterland. He went to Fraser Island on two occasions; once with Barrie Reid soon after he arrived and again with poet Judith Wright and her husband Jack McKinney in October – Nolan stayed for about a month, Wright and McKinney for just three days.5 Nolan flew from Brisbane to Sydney on New Years Eve and letters from that time indicate confusion as to his intentions.6 Any confusion was resolved by 25 March 1948 when he married John Reed’s sister Cynthia in St Stephen’s Presbyterian Church in Macquarie Street, thereby effectively fracturing all bonds between the two couples. The marriage certificate records Fraser Island as his usual place of residence!

The Moreton Galleries Exhibition

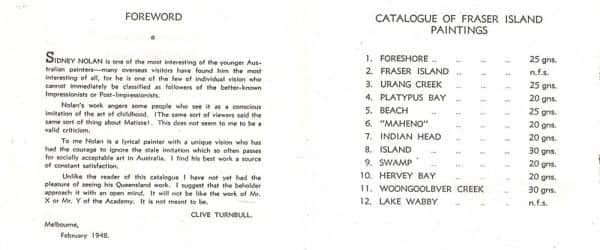

In February 1948 a dozen of Nolan’s Fraser Island works were exhibited at Moreton Galleries in Brisbane.

3. Sidney Nolan, Catalogue of Fraser Island Paintings, The Moreton Galleries, Brisbane, February 17th to 28th, 1948

NOTE that since this article was posted in 2012, further information has come to light regarding the history, identity and whereabouts of a number of the paintings mentioned here. Consequently a little updating is necessary. However rather than editing the existing article, a short summary is provided in this endnote.7 It is suggested that this endnote be read before continuing, so that the sense of the original can be retained whilst allowing it to be read in light of this further information.

As well as the work now known as Mrs Fraser, eleven other paintings were on display at prices ranging from 20 to 30 guineas. Two of the twelve were not for sale, and one of these, Fraser Island, the second image in Figure 4 below, had been bought by Judith Wright.

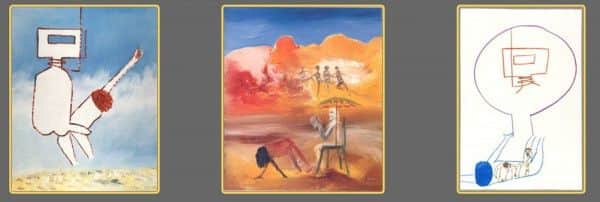

4. Five of the twelve Sidney Nolan works exhibited in the 1948 Moreton Galleries exhibition. One of the black and white images is probably No 5 “Beach”. The identity of the other black and white image is uncertain. The colour images, from left to right, are: No 2 “Fraser Island”; No 12 “Lake Wabby” and probably No 10 “Hervey Bay”

The exhibition was received, in the main, with disbelief and incredulity. The newspapers were derisive: one stating ‘The only excuse I can find for Mr Nolan’s blatant extremism and what appears to me to be deliberate maltreatment of so much useful and hard-to-come-by building material (all his ‘works’ are on masonite), is the artist’s lack of maturity. With youth’s love of self exhibition he has employed all the tactics of shock. These monstrous daubings … simply defy description’8; another, under the headline I’m Not so Artful states, ‘Now mind you, I’m not disputing it. All I want to do is point out my own abyssmal ignorance of the subject by describing what my untrained eye observed, at a recent art show. Picture number 4 at the show was called ‘The Creek’. It depicted a woman (I think) down on all fours among a clump of mangroves, obviously looking for something. The woman (who had no clothes on) was apparently in need of a good feed. There was no sign of any creek.’9 In her letter to the editor, Judith Wright responded to the critics saying ‘Mr Nolan’s painting, though like all vital work, a subject of controversy, is recognised by the best Australian criticism as among the most important being done by the younger group of painters. To dismiss it in an hysterical and ill-balanced attack, such as that which appeared in your paper, is to display a provincialism which is a disgrace to Brisbane’s standards of judgement.’10

As can be seen in Figure 3, the title of exhibit number 4 is Platypus Bay rather than ‘The Creek’. Two exhibits include ‘creek’ in their title – No 3 Urang Creek and No 11 Woongoolbver Creek, and from the description of the painting in the newspaper critique it seems reasonable to assume that the painting we know as Mrs Fraser is one of these, most likely Urang Creek, as this allows for a numbering error of only one. 11 For ease of reference, this paper will henceforth refer to the early version of Mrs Fraser as Urang Creek. [But NOTE, as in Endnote 7 above, that the correct original identification is Woongoolbver Creek.] The newspaper critic who could find no sign of a creek had most likely never set foot on Fraser Island, for had she, she would probably have landed at the mouth of Urang Creek on a high tide, as it would seem did Nolan and Reid,12 to find that as the tide ran out Urang becomes ‘a shallow small creek that completely dries at low tide. The grey sand in the creek bed has the consistency of mud, and is not friendly to walkers. The log dump, a wharf ramp of logs laid in the white sand, lies 80 meters away …..’13

Urang Creek, Fraser Island, looking downstream at low tide

Structuring ways of seeing ‘Mrs Fraser’

The painting was not exhibited for another 9 years, next appearing in 1957 at Bryan Robertson’s Whitechapel Art Gallery in London. The first painting listed in the catalogue, it appears for the first time under its present title Mrs Fraser and, erroneously it would seem, is referenced as having been No 9 Swamp in the 1948 Moreton Galleries exhibition.

This work is singular in Nolan’s ouevre as a catalyst generating passionate responses in viewers; responses which, like the various narratives that over time have characterised the manner and style of reportage of the historical Eliza Fraser, have been preconditioned by structured ways of seeing. This preconditioning, coupled with a doctrine (of sorts) of precedence in critique, has in turn influenced critics and curators, leading to a structuring of commentary that has encouraged viewers to see the work itself, to see Eliza Fraser, and in time to see Sunday Reed – to the extent that this has been influenced by connotations of her in association with the painting – in particular ways.

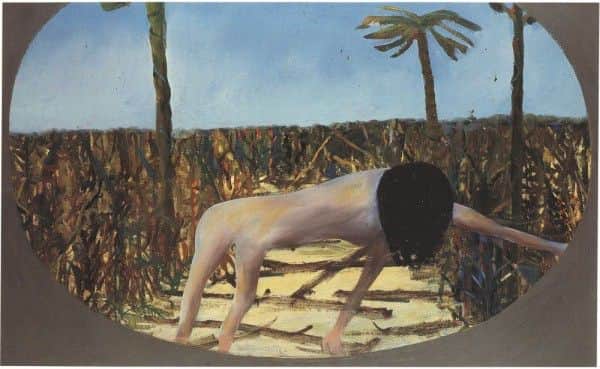

Eliza’s bad press, as associated with the Nolan painting, began with Colin MacInnes who wrote in the 1957 Whitechapel catalog: ‘this “betrayal” theme – in which the traitress is portrayed naked in grotesque postures, and the stripes of her savior’s convict dress in skeltonic bars – is evidently one that preoccupies the artist, since he has returned to it in the present year (1957).’14 The bad press continued in 1967 with Nolan’s close friend, the critic and artist Elwyn (Jack) Lynn, writing “He led her to civilisation, but her nakedness and gentility led her to announce that she would betray Bracefell if he did not go bush and so conceal the fact that she had been for so long almost nude in his company. ….. Mrs Fraser, scrambling naked through the undergrowth is too bitter a symbol for a mythical subject, for myth tends to take the bitterness out of life.”15 In 1971 the prejudicial bar was raised several notches by another of Nolan’s friends, art critic and journalist Robert Melville, who opined of the painting ‘The image of Mrs Fraser is peculiarly provocative. Her plight arouses not pity but the sense of her openness to sexual assault. She is a woman likely to be taken from behind, like the women in some of the Pompeian wall paintings, with no preference and no certainty on the part of the taker as to which passage is being penetrated. She would spit and snap like a female dingo, without offering resistance.”16 Finally, in the catalogue for the recent Nolan retrospective, Barry Pearce wrote that the work “depicts a naked female form on all fours, dog-like, vagina exposed, face hidden by a mass of dark dishevilled hair, reaching across a sandy creek bed …”17

With differing perspective, in 1986 Jane Clark wrote of Mrs Fraser “She is utterly vulnerable within the unflinching focus of his oval painted frame: as though seen through binoculars or down the barrel of a gun.”18 Then in 1995 when investigating representations of masculinity and femininity, self and other in the Eliza Fraser story, Kay Schaffer spoke of first encountering Nolan’s painting: ‘My first surprised view of this painting, which I remembered seeing big and bold, on the cover of a book of art criticism – the masculine possessiveness of the gaze and the extreme vulnerability of this debased, feminine creature – struck me like a blow to the chest, evoking feelings of both anger and vulnerability.’19 These feminine perceptions are characterised by words like ‘vunerable’ and ‘debased’ and contrast sharply with the language of male commentary: ‘traitress’, ‘naked’, ‘grotesque’, ‘nude’, ‘provocative’, ‘penetrated’, ‘taken’ and ‘dog-like’.

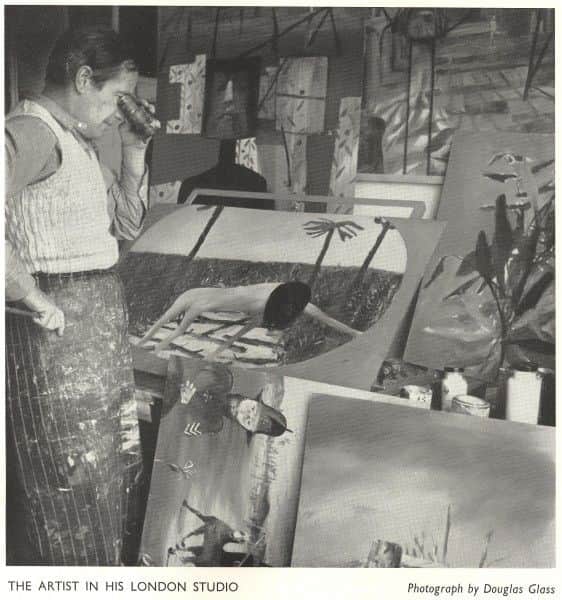

With critics and commentators fostering the notion that Mrs Fraser had been painted , if not with malice aforethought, certainly with betrayal in general and Sunday Reed in particular in mind, over the years Nolan himself did little to allay these impressions – indeed he can be seen as having encouraged the belief. At the time of the 1957 Whitechapel exhibition he said “There is something bizarre about a nude with white skin in the lush darkness of a forest”20 and the exhibition catalogue concludes with a photograph of Nolan, paintbrush in hand, peering through reversed binoculars at Mrs Fraser positioned on his easel. Thus the artist too can be seen as structuring ways of seeing.

In both painting and poetry Nolan frequently returned to his years at Heide and to what he increasingly saw as Sunday’s Eliza-like betrayal. In 1987 he said in an interview: ‘I’d just been through an experience in Melbourne which had gone on for some years in which I’d felt … this lady had not been up to scratch. Done me wrong. Which I still feel. …. My ex-friend Patrick White went up to Fraser Island to write a book about Mrs Fraser. But he twisted the story on its head. She’s full of nobility and Wordsworth. She ends up knitting. In fact, she was a bitch.’21 Two years later he had shifted ground somewhat saying in another interview ‘but now I have to rethink her, seeing her history …. now I begin to think I can paint her among the Stone Age cultures of Orkney; I begin to think of her, from this place, going through an experience in an even older culture.’22 This Mrs Fraser motif, the crawling figure on all fours, he uses time and again in later works – perhaps none more bitter than the 1974 Ern Malley series (which says far more about his feelings for Heide than about the hoax poet),23 or none more sardonic – given Robert Melville’s “Paradise Garden” essay – than the 1985 painting “Robert Melville at Alice Springs” with a Mrs Fraser figure crawling past a seated Melville, reading beneath an umbrella in the Australian red centre.

9. Sidney Nolan, examples of subsequent use of the Mrs Fraser motif. From left to right: ‘Beyond is Anything’ 1974, Art Gallery of South Australia; ‘ Robert Melville at Alice Springs’, 1985; ‘Baroque Exterior’, 1974, Art Gallery of South Australia

Reconstructing ‘Mrs Fraser’

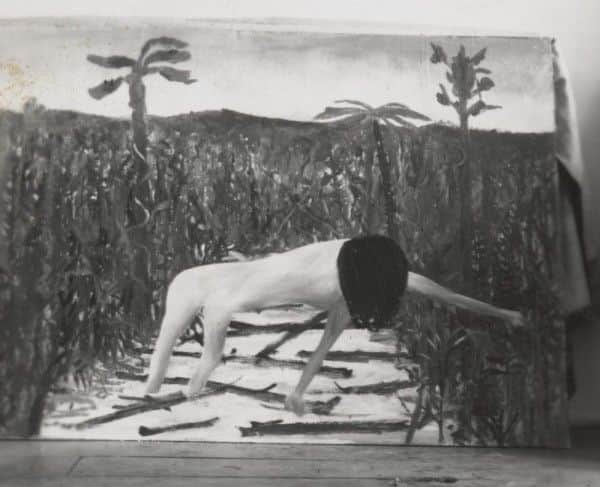

The more I researched the Nolan/Reed relationship, the more convinced I became that his Mrs Fraser was not painted with any malice directed towards Sunday Reed. Then, whilst researching the Reed Papers at the State Library of Victoria in 2009, I discovered two hitherto unreported photographs of paintings which Nolan sent to the Reeds from Fraser Island.24 The photos lay in two envelopes; one inscribed in John Reed’s hand ‘Photographs taken by Nolan on his trip north with Barrie’, the other inscribed in Sunday’s hand ‘Nolan. photos …. from the north in letter to me’. One of the two small black and white photos is shown in Figure 10. Taken in conjunction with other evidence, it makes me quite certain that Robert Melville is incorrect when he opined in 1971 (perhaps with some encouragement from Nolan): ‘he may have had some other woman in mind when making his imaginary portrait of her [Mrs Fraser]’.25

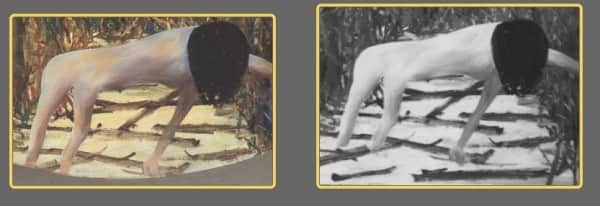

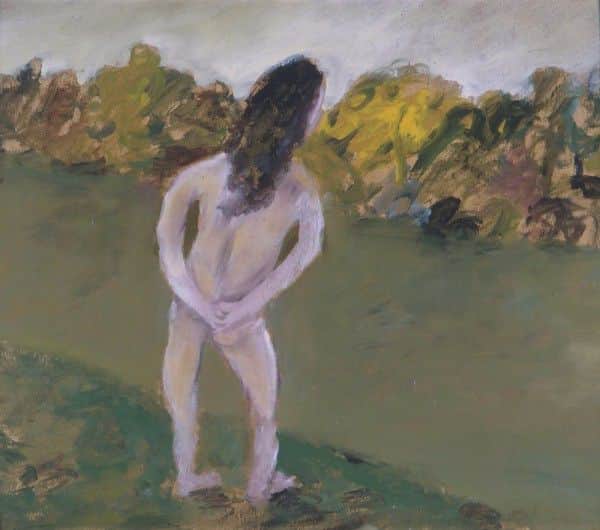

The photo reveals an earlier Mrs Fraser without a tondo and which is about four inches higher wherein we see all three treetops and a high horizon.26 Computer enhancement of the old black and white photo reveals a work of pathos and beauty – and of no small significance.

I can find no evidence suggesting anything other than that the Urang Creek/Mrs Fraser work remained in Nolan’s personal possession until the Queensland Art Gallery purchased it from his estate in 1995. Whilst the Whitechapel catalogue does not list its provenance, the 1961 Thames and Hudson monograph “Nolan” lists it as being in the artist’s collection.27 It seems to me unlikely that Nolan ever parted company with this work which had become for him a talisman to which he forever looked back, whether through his binoculars or through the prism of his mind.

When though was the original Urang Creek transformed into today’s Mrs Fraser?

Clearly before the Whitechapel exhibition in 1957 – but in which form was it hung in the Moreton Galleries in 1948? Barbara Blackman, then 19 and co-editor with Barrie Reid of Barjai, saw the 1948 exhibition and whilst not recalling details of the works, certainly cannot recall a work framed within a painted oval tondo. 28 Although not verified definitively, relying on Barbara Blackman’s certainty that there was no oval tondo framing in the exhibition – and she has extraordinary visual recall from her sighted years – it would seem most likely that it was in its original format when hung in the Moreton Galleries.

How the original was altered is perhaps best examined by considering the three major changes to Urang Creek: the addition of the tondo, the removal of the top four inches and the lowering of the horizon. Two sequences of alterations are possible commencing with removal of the top portion (Figures 12 and 13). However it seems unlikely that this would have been the first alteration as it implies that the oval was intentionally painted without an upper side. Taking this into consideration together with the fact that a number of paintings in Nolan’s personal possession were water damaged and some of these were renovated by cutting away the damaged side,29 it seems reasonable to assume that the top portion was removed after the tondo was painted in.

Furthermore the original Urang Creek is a well balanced composition and it is unlikely Nolan would have decided to lower the horizon as the first step. (See the sequence of alterations shown in Figure 14.)

Accordingly it seems reasonable to conclude it is most likely that the oval tondo was added before other alterations were made to the original. On several occasions Nolan used the tondo device – perhaps to give an emphasis, perhaps to indicate persons or places of moment – in manner similar to the well known Carjat photograph of Nolan’s hero Rimbaud. Examples of Nolan’s use of the tondo are seen in Figures 15 and 16.

15. Nolan works using a tondo, from left to right: (1) “Landscape, Dimboola”, 1948; (2) “Moonboy” or “Boy and the Moon”, 1939-40, National Gallery of Australia; (3) “Homage aux Prix Nobel”, 1974; (4) “Mrs Skillion putting her fingers to her nose”, c 1946-47.

16. Nolan works using a tondo – flanking Carjat’s photograph of Nolan’s hero Rimbaud, from left to right: (1) “Ned Kelly”, c 1946, National Gallery of Australia; (2) “D H Lawrence”, c 1940; (3) “The Sisters”, 1946; (4) “Portrait of Barrett Reid”, 1947, Queensland Art Gallery.

The horizon might seem a little cramped with a tondo painted on the original, but not excessively so. Whilst it is possible the skyline could have been lowered at the same time the tondo was painted, this sequence of alterations (Figure 17), seems the least likely of the two options possible when painting in the tondo is the first step.

In my view the sequence most likely to reflect the transformation of Urang Creek into Mrs Fraser is that shown in Figure 18 below. Nolan added the tondo at some stage between when Urang Creek was first painted in 1947 and when it appeared at the Whitechapel Art Gallery ten years later – and if the painting was damaged, the tondo was almost certainly added before this happened. It is unlikely the horizon would have been lowered before the upper portion of the original painting was removed, as shown in the third image in Figure 17 above. However once the probably damaged top portion was cut away leaving the third image in the sequence of alterations shown below, the need to do something about the horizon line is obvious. Who knows, perhaps Nolan added the finishing touches just before the work was photographed on the easel in his London studio.

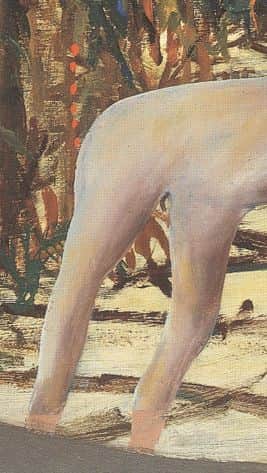

Another, if less obvious, alteration is evident on closer examination of the legs. Looking at the comparison in Figure 19, in the original version on the right, both legs are shown entering the water at approximately the same level above the stick – thus suggesting that the formost leg could well be the left leg. In the final version on the left, the lower portions of the legs are painted in a quite different creamy tone and extend over the stick to the edge of the tondo – thus suggesting quite clearly that it is the right leg which is foremost. The right arm also appears to have been overpainted in the same creamy tones from near the elbow. These alterations could have been done at quite an early stage to give the impression of the limbs being in water – the clarity of the water on Fraser Island having been a revelation to Nolan. He wrote from the island to Laurence Hope: ‘Have returned to the island for a while and returning has been, as it so rarely is, a real return & in the two days here have once again got caught up in its spell. There are many aspects to talk about, but most of all this time I think, I have been affected by the clearness of the water in the lakes and creeks. In one of the lakes it is impossible to tell where the water meets the white sand. Your feet find themselves in water while your eyesight swears you are still walking on sand. This is the kind of purity one sometimes wishes for painting.’30

19. Comparison of the Mrs Fraser figure in (left) “Mrs Fraser” and (right) “Urang Creek”

The apparent repositioning of the legs may be why some commentators have seen anatomical references in Eliza’s posture. Be that as it may, a closer examination of the extant work, as seen in Figure 20 below, makes it quite clear such referencing is unwarranted – the feature is clearly of botanical origin.

Deconstructing ‘Mrs Fraser’

Several factors suggest revision of the notion that in 1947 Nolan painted the work we now know as Mrs Fraser with a malevolent intent to denigrate Sunday Reed, or that the painting was merely the first salvo in a barrage of bile culminating in his 1971 book of poems Paradise Garden. Prime among these factors is what can be learned from a close analysis of the reconstructed Urang Creek. Other factors include the atmosphere in which the work was created; the content, tone and even addresses used in the contemporary correspondence; the development of the rift between Nolan and the Reeds, and the provenance of one of the paintings in the Moreton Galleries exhibition.

Nolan most likely first became aware of the Eliza Fraser story from Barry Reid upon arriving in Brisbane.31 His sources, apart from Reid, would most likely have been books in the Oxley Library in Brisbane: the 1838 book The Shipwreck of the Stirling Castle by John Curtis,32 the 1888 book The Genesis of Queensland by Henry Stuart Russell33 and Robert Gibbing’s 1937 book John Graham, (Convict).34 These sources would have given him a somewhat mixed picture – Russell’s more the Bracefell story with Eliza as betrayer, the other two more sympathetic and in the captivity narrative vein. In each of them Elisa’s plight is graphic. Curtis records she ‘felt her brain swim, and a sound in her head like the ringing of bells. …. [She] fell to the ground completely petrified and bereft of sense’ and on more than one occasion she falls into ‘a swoon of insensibility.’35 Russell tells how ‘she was compelled to drag in wood for fires, and fetch water with as much cruelty as the “gins” themselves. ….. Her sufferings were terrible: ……. Her misery and want would soon have killed her.’36 Gibbings quotes from Eliza’s own account ‘We were now portioned off to different masters, who employed us in carrying wood, water and bark, and treated us with the greatest cruelty,’ and continues his own narrative ‘Naked and helpless she was dragged from camp to camp, compelled to carry other women’s children or her shoulders, to cut wood, fetch water and catch fish. …. when gathering firewood she was compelled to bend down and collect it with her hands instead of just picking it up with her toes as she went along ….’37

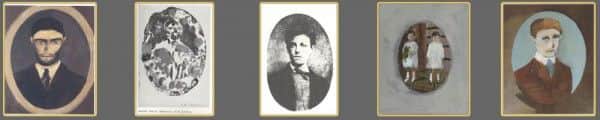

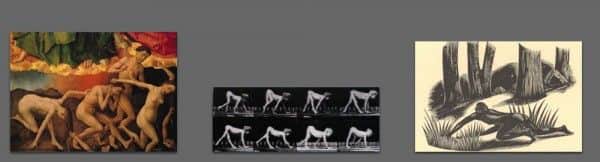

These then were the type of accounts Nolan would first have read regarding Mrs Fraser. Moreover should he have read the Gibbings book – and this is likely for the book would have been known in Australian research libraries; Gibbings researched it at the Mitchell Library in Sydney and it is dedicated to the Mitchell librarian, Ida Leeson – he would have been aware of Gibbings’ woodcut image of a crawling Eliza Fraser, the third image in Figure 21 below.38 Other images possibly seen by Nolan before he went to Fraser Island are also illustrated in Figure 21. Years later he commented to Jack Lynn on the resemblance of the Mrs Fraser motif to the crawling nude among the damned in the van der Weyden altarpiece in the Hotel Dieu, Beaune,39 and Melville drew to attention the Eadweard Muybridge kaleidoscope in his essay “Disquitening Muse” in Paradise Garden.40

21. Resembling “Mrs Fraser” – possible predecessors, from left to right: (1) detail from Rogier van der Weyden “Altarpiece of the Last Judgement”, c 1452; (2) Eadweard Muybridge “Infantile Paralysis: Child Walking on Hands and Feet”, 1887; (3) Robert Gibbings, illustration from “John Graham (Convict)”, 1937

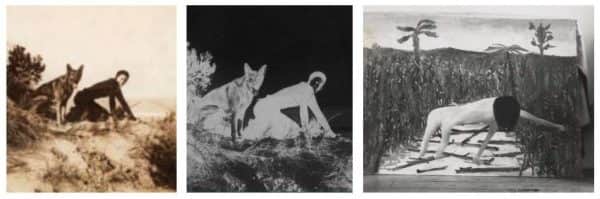

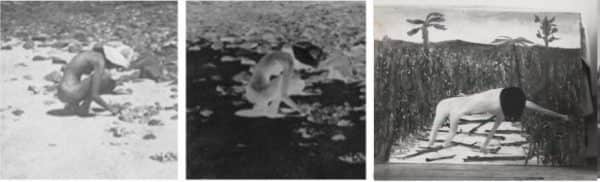

NOTE. Since this article was posted in April 2012, Lesley Harding and Kendrah Morgan’s book Modern Love:The Lives of John & Sunday Reed has been published and includes two photos which can be added to the above as possible predecessors. One depicts a crouching Sunday about the time of her wedding to John Reed in 1932, the other shows a naked Sunday beachcombing on Green Island in 1946.41 It is reasonable to assume Nolan would have seen both photos, which may have been tucked away in his visual memory to influence the imagery seen in the painting we now call Mrs Fraser.

It seems not unreasonable to accept that the image we now see in Urang Creek – an uncropped Mrs Fraser sans tondo – was painted with no more stimulus than that derived from the stories of hardship Nolan would have heard and read. As Barrie Reid wrote in 1967 speaking of his time with Nolan 20 years earlier: ‘Somewhere the story of Mrs Fraser as told in John Curtis’s The Wreck of the Stirling Castle [Lond., 1838] took on a vivid life in our talks. … Mrs Fraser naked in the mangroves, merged in the rain forest, was an historical actuality which contained for Nolan a dynamic poetry and focus for vision.’42 This, coupled with the possibility he may well have been aware of visual images similar to the Mrs Fraser figure,43 suggests it was quite unnecessary in the genesis of the work for an additional stimulus stemming from a personal malevolance. Indeed in looking for possible progenitors for the work, it is difficult not to be drawn to the 1945 work The Bather seen in Figure 22. The work has a certain presience. Suggested as being related to the bathing figure in the first Kelly series painting The Questioning,44 but most probably depicting someone about to dive into the muddy waters of the Yarra at Heide, it can also be seen, perhaps a little fancifully, as relating to a future Mrs Fraser – Eliza standing beside the waters of Urang Creek across which at low tide she must crawl to the mangroves on the bank beyond. The Bather is then tucked away in Nolan’s eidetic memory to await release, the figure now on all fours, two years hence.

Nolan’s letters from Queensland to John Reed45 are instructive as to the nature of Nolan’s relationship with the Reeds at the time, particularly his relationship with Sunday.46 From the island Nolan wrote ‘I doubt I have given good picture (sic) really of the island, it has been more intense than I have written; the psyche of the place has bitten me deeply and I feel involved with it in a way that I cannot explain easily. … there are many things I wanted to tell Sun out of the island but somehow do not feel they can be said at present. Finding our own particular island must come first. My love to her and to Sweeney.’47 Of his own inner turmoil he had written to John a few days earlier ‘My reality in relation to Sun will never break. There may be elements of obsession I have carried around since boyhood, but there is nothing I know can persist finally in the face of the reality I know with Sun. You know as well as I do that love with Sun is final, that one does not ever approach the world again except that finality.’48 Soon after this letter he contemplates painting what would become his Mrs Fraser series: ‘It has been on my mind to follow the story of the convict and Mrs Frazer (sic) on their journey down from Frazer Island down to Brisbane. … I look forward to a letter tonight you must write all details are crucial now we must learn to remake what has been undone. I have a start in myself, I learn gradually how I have lived with a sword in my hand and heart.’49 Back in Brisbane from Fraser Island he wrote ‘My thoughts however had not taken me to returning to Heide. Whatever else comes or goes that has been a reality constant for me since I left. I did not know where the next stop would be but I know I cannot live again next to Sun unless, to put it simply, it is next to the reason for being born. Coming back to Heide without bringing that truth into being is as impossible for me to anticipate as it is for Sun.’50 His relationship with the Reeds remained open and apparently friendly, if restrained, and they continued to provide him with financial support. From Green Island he wrote ‘I will have to ask you to post if you can next months cheque with the letter to Brisbane. Going down from here will leave me too little to proceed into Sydney. If that is decided upon.’51

His mention of Sydney becomes clear when read in the light of a letter Barrie Reid wrote to Laurence Hope who was working in Sydney at this time: ‘Sun has telegrammed for me to come to Melbourne – which, like Sun as always, was just at the proper time. So Charles and I will hitchhike there from here and will probably start next Monday. Nolan probably leaves here for Sydney by plane on this Wednesday. He will let you know. He intends to stay there and then pick us up on our way thru.’ Suggesting to Hope that he not continue on to Melbourne with them, he says: ‘the arrival of 3 of us will be quite a lot for Sun to experience; 4 is a bit much.’52 Nolan’s mention of Sydney may well be not so much an indication of an intention to seriously consider residing there, but simply to pay a visit when returning to Melbourne. A further indication that he was far from certain of his intentions or his movements was the letter he wrote on 19 January 1948 to Albert Tucker in London, wherein he lists his address as ‘c/o John Reed, Templestowe Rd, Heidelberg.’53

From Sydney, Nolan soon wrote to the Reeds ‘Once again will have to ask you if you can to send cheque before end of month.’54 In this letter he would continue ‘I can perhaps make arrangements here in Sydney about showing the Kelly’s [sic]. I do not even feel that the Kelly’s belong to anyone else other than Sun and I cannot visualise in what way I could exhibit them. We can discuss it anyway but one has to start anticipating now some action that will take place months ahead. Painting has become a fairly quite thing for me now. Apparently my life is to be bound up with it for good and all and once you know this it brings a quietitude which can wait its time. Perhaps I feel this about all my living now, for myself I know where my love is and what it is about and it does not seem to be an alone thing. My love to you both and to Sweeney and to Heide & to you [sic] happiness in it.’ Early in February he wrote ‘My love to you both and the desire for that to be something tangible and of use.’55

All this material suggests that his relationship with Sunday Reed, whilst obviously not what it was once, remained warm while he was in Queensland – indeed for some time after that. However what convinces me more than anything that Urang Creek was not painted with Sunday Reed in mind is that he gave Lake Wabby, the fourth of the images in Figure 4 above, to Sunday for Christmas that year. The work is inscribed ‘Lake Wabby/Oct.47./N/Frazer Island./For Sun/Xmas1947/Nolan’ with its provenance listed as ‘The artist, to Sunday Reed 1947’56

It is difficult to think Nolan would have imbued the painting, at its creation, with the sort of denigration of Sunday Reed that subsequently he and his minions went to some lengths to attach to the work, given that he gave to Sunday another work hanging with it in the Moreton Galleries exhibition. His gift is probably why the catalogue lists Lake Wabby as not for sale.

As fascinating and instructive as it may be to chart the deterioration of the relationship between these two lovers – a deterioration which, like the relationship, so shaped their lives – this is not the place to do so and we can but wait for biographies of Nolan and of the Reeds to appear. Sufficient here to note that two factors serving to alienate Sunday in Nolan’s eyes would have been, firstly, the Reeds’ reaction to his sudden and unexpected marriage on 25 March 1948 to John’s sister Cynthia,57 and secondly, in early 1957, their resistance to Bryan Robertson’s request for the return from loan (as he put it) of all Nolan’s pre-1948 works for the Whitechapel exhibition.58

Conclusion

To conclude on a poignant note:

Barrie Reid, with whom Nolan first visited Fraser Island, died in August 1995 exactly a month before the anthology of his poetry, Making Country, was launched at Heide,59 where, by provision of the wills of John and Sunday Reed, he had been custodian for his lifetime. Just days before he died he was given a prepublication mockup of the book, and on this mockup he made personal comments and notes.60 Against the poem “Letters of the Artist” he has annoted: ‘After I read late at night at Heide Nolan’s beautiful love letters to Sun. She was distressed because of one of his nasty TV attacks on her.’ “Letters of the Artist” incorporates a love poem Nolan wrote to Sunday – most likely during his army service in the Wimmera.

We walked here

remember.

Somewhere near

the creek began to run,

its scent like your caress, warm in the sun.

Somewhere here the bush began.

The leaves close to us,

only the birds

saw us looking,

only the creek

ran with us,

only the scent, warm,

caressing, saw our caress.

The sunlight

on the creek shines on me,

your scent touches me

and years of parting

part the bush for me.

The poem immediately before this is “The Artist” against which Reid has written: ‘Nolan of course.’ “The Artist” concludes with the lines:

Now night comes, now your slow

eye learns new tricks. Old

tricksters feel the cold,

move fast. Don’t look now

Herr Dr Conjurer.

Your slight of eye

slays us and memory.

One cold look

and rose, window, disappear.

We find them in a book.

The book to which Reid refers is “Paradise Garden”. Published in 1971 by his friend and latter-day patron Lord Alistair McAlpine, the book is a lavishly produced collection of the bitter poems Nolan wrote drawing on his Heide days and their aftermath, and is illustrated by him with crayon sketches on transparent overlays above the poems to sit opposite reproductions of flower paintings from his Paradise Garden work. The book accompanied a film of the same name produced by Stuart Cooper with narration and recitation by Orson Welles.61 An example of the invective in the Paradise Garden verses – if anything somewhat milder than that in many others – is the poem “Dead-heading,” seen in Figure 23 below with a Mrs Fraser-like motif central in the transparency. By the time of Paradise Garden, Nolan’s feelings for Sunday had certainly gone full circle from the langourous first lines of his love poem: ‘We walked here / remember.”

In reconstructing the painting we now know as Mrs Fraser, this paper has shown that the work began its life in an atmosphere which, if not exactly the same as when from the Wimmera he wrote love poems to Sunday Reed, was certainly more akin to it than to the overt animosity of the Paradise Garden verses – an animosity with which Nolan’s Mrs Fraser work has long been associated.

ENDNOTES

- An account of the breakup of Nolan’s first marriage, told from his wife’s perspective, appears in Frances Lindsay’s essay Sidney Nolan: the end of St Kilda Pier in the catalogue Sidney Nolan, AGNSW, 2007.

- National Archives, http://vrroom.naa.gov.au/print/?ID=19576.

- Barrie Reid, ‘Nolan in Queensland; some biographical notes on the 1947-8 paintings,’ Art and Australia, Vol. 5 No. 2, Sydney, September 1967, p. 447. In January 1947 Nolan wrote a poem ‘Prince on a Hill’ for Barrie Reid with the line ‘they cannot be forever’. In Nolan’s hand, the manuscript is in the Papers of Shelton Lea, Australian Manuscripts Collection, State Library of Victoria, MS 13526, Box 10, File 3(c).

- Nolan discusses leaving Heide in an interview with Michael Heyward in May 1991. Of Sunday Reed’s attitude he said “She could never see the logic of why I left … but I couldn’t see the logic of staying”. See Sidney Nolan, Interview Michael Heyward, 5 April 1991, Papers of Michael Heyward, Australian Manuscripts Collection, State Library of Victoria, PA 96/159, Box 5.

- Michele Anderson, Barjai Miya Studio and young Brisbane artists of the 1940s: Towards a radical practice, Thesis, University of Queensland, July 1987, footnote 114, p. 150-151. See also Judith Wright’s address to the 1975 Fraser Island Environmental Inquiry http://www.fido.org.au/moonbi/backgrounders/35%20FI%20a%20cultural%20monument.pdf. Note also that Nolan wrote to Bert Tucker in London of his impressions of Fraser Island. See Sidney Nolan, Letter to Albert Tucker, Sydney, 6 November, 1947, published in Bert & Ned, Meigunyah Press, Melbourne, 2006, p. 67.

- Sidney Nolan, Letters to John Reed after he left Heide on 8 July 1947, Papers of John & Sunday Reed, Australian Manuscripts Collection, State Library of Victoria, MS 13186, Box 2, File 6.

- The following identifications are definitive, as advised by Nolan authority Geoffrey Smith (email to the writer, 3 February 2014.) The painting now known as Mrs Fraser, now at QAGOMA, is a slightly modified version of Moreton Galleries catalogue listing (MGCL) No 11 Woongoolbver Creek. The painting sold at the exhibition to Dr Lofkovits was No 9 Swamp, but neither Swamp nor No 2 Urang Creek became Mrs Fraser. The correct identification of the five works illustrated immediately below is, from left to right: (1) MGCL No 1 Foreshore; MGCL No 8 Island; MGCL No 5 Beach (detail); MGCL No 12 Lake Wabby; MGCL No 4 Platypus Bay.

It should be noted that MGCL No 8 Island, now at AGNSW, has long been known and until very recently exhibited under the title Fraser Island, whereas MGCL No 2 Fraser Island was given by Nolan to the Forestry overseer with whom he stayed on the Island, thus accounting for its designation n.f.s in the catalogue. MGCL No 4 Platypus Bay, now at QAGOMA, was exhibited at QAG in 1989 as Landscape. Further posts regarding Nolan’s Fraser Island paintings exhibited at the Moreton Galleries in 1947 are available on this website. See Re-discovered Nolan images include a second 1947 “Mrs Fraser” posted 25 January 2014, and Auction of significant Nolan painting posted 9 August 2014.

- Elizabeth Webb, Courier Mail, Brisbane, 18 February 1948.

- Joyce Stirling, Telegraph, Brisbane, 17 February 1948.

- Judith Wright, Courier Mail, Brisbane, 19 February 1948.

- Just which painting is which in the Moreton Galleries catalog and exhibition is far from clear. Of the painting we now know as Mrs Fraser, the 1957 Whitechapel catalogue says it is No 9 Swamp; Jane Clark says it is No 2 Urang Creek (Jane Clark, Sidney Nolan, Landscapes and Legends, a retrospective exhibition: 1937-1987, International Cultural Corporation of Australia, 1987, p. 91.); critic Joyce Stirling’s description is certainly of Mrs Fraser, but she says it is No 4 The Creek (Telegraph, 17/2/1948); and Barry Pearce says it is No 2 Fraser Island (Barry Pearce, Sidney Nolan, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 2007, p. 233.). Of the painting we now know as Fraser Island, Barry Pearce says it is No 8 Island (Nolan, ibid.), as does Jane Clark having checked with the owner Judith Wright (Landscapes and Legends, ibid.). According to Joyce Stirling, exhibit No 5 is called The Island (Telegraph, 17/2/1948), and she describes a work she calls The Beach as if describing the painting in the other photograph Nolan sent to the Reeds (image on the left in Figure 4). However a photo appearing in the Courier Mail article on 19/2/1948 (centre image in Figure 4) is called The Beach in the newspaper, and Joyce Stirling’s comments could apply to either. Finally Jane Clark notes that Platypus Bay and Hervey Bay are in private collections (Landscapes and Legends, ibid.). Regarding Hervey Bay, the catalogue for the Queensland Art Gallery 1989 exhibition Nolan’s Fraser includes a work Landscape which is dated 1947 and which I suspect is No 10 Hervey Bay in the Moreton catalogue. The work is very naturalistic and looks remarkably like the view from a high point behind Urang Creek, out over Hervey Bay with its Little Woody and Woody Islands, and across to the mainland beyond. Nolan loaned three works to the QAG exhibition: Landscape/Hervey Bay, Fraser Island and Mrs Fraser; and Lake Wabby came from Heide. Perhaps photographs from the Moreton exhibition exist – but I have seen none, although I have yet to inspect Peter Skinner’s thesis John Cooper and the Moreton Galleries: a study of a Brisbane art dealer and gallery owner 1933-1950, copies of which are held in the Queensland Art Gallery Research Library and the University of Queensland Library.

- Barrie Reid relates ‘There was no jetty at Fraser …. That night the barge lay off the coast and on the early-morning tide we went up a small creek,’ Art and Australia, Vol. 5 No. 2, op. cit., p. 447.

- Notes from article on the wreck of the S.S. Essex at the mouth of Urang Creek: see online magazine “Upstream Paddle Magazine” Issue No 4, Summer 2007, page 11, http://www.upstreampaddle.com/media/Essex%20wreck,%20Fraser%20Island.pdf.

- Colin MacInnes, Sidney Nolan: The Search for an Australian Myth, Whitechapel Art Galley, London, 1957, p. 16.

- Elwyn Lynn, Sidney Nolan – Myth and Imagery, Macmillan, London, 1967, p. 31.

- Robert Melville, Paradise Garden, R. Alistair McAlpine Publishing Ltd., London, 1971, p. 7.

- Barry Pearce, Sidney Nolan, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 2007, p. 36.

- Jane Clark, Sidney Nolan, Landscapes and Legends, a retrospective exhibition: 1937-1987, International Cultural Corporation of Australia, 1987, p. 91.

- Kay Schaffer, In the Wake of First Contact, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1995, p. 15.

- Sidney Nolan, Vogue, London, June 1957; reported in Jane Clark, Sidney Nolan – Landscapes and Legends, op. cit. p. 91.

- Sidney Nolan, interview Anne Kelleher, Harpers Bazaar Australia, 15 December 1987.

- Sidney Nolan, interview Nicholas Rothwell, The Weekend Australian, 15-16 July 1989.

- See the essay “The Illuminating Ecliptic” by Elwyn Lynn in Sidney Nolan and Ern Malley, The Darkening Ecliptic, R. Alistair McAlpine Publishing Ltd., London, 1971, p. 14.

- Sidney Nolan, two photographs of Fraser Island paintings, 1947, Papers of John & Sunday Reed, Australian Manuscripts Collection, State Library of Victoria, MS 13186, Box 16, File 1.

- Robert Melville, Paradise Garden, op. cit., p. 6. Nolan would seem to have taken little notice of Albert Tucker’s early assessment of Melville. On Christmas Day 1947 Tucker wrote from London to Nolan describing Melville as “a disappointing little man with buck teeth and with all facets closed to communication, with no umbilical cord, all bound up, hag-ridden with custom, no value judgements, all social strategic, afraid of people ….”. See Albert Tucker, Letter to Sidney Nolan, London, 25 December, 1947, published in Bert & Ned, Meigunyah Press, Melbourne, 2006, p. 74.

- A scaling from the photo of the original, given that the extant Mrs Fraser measures 66.2 x 107 cm, indicates that the original was approximately 76 x 107 cm or 30 x 42 inches in the old Imperial scale – the same size as Lake Wabby and Fraser Island. This board size is produced by cutting a 5 ft x 7 ft sheet of Masonite into four and it is interesting to speculate that these sheets may have come from the World War 2 Commando Training School huts inland from Mackenzie’s Jetty a few kilometers south of Urang Creek. This was not a standard size for Masonite sheets, but checks are proceeding as to whether it was standard issue for Army huts.

- Colin MacInnes and Kenneth Clark, Nolan, Thames and Hudson, London, 1961, p. 73.

- Conversation with the author, February 2012. Other Brisbane identities who would almost certainly have seen the exhibition and who are yet to be contacted are Charles Osborne, Laurence Hope and Mary Christina St John.

- I am indebted to Damian Smith, who was archivist for the estate of Sidney Nolan and lived at the Rodd between 1996 and 1999, for this advice.

- Sidney Nolan, letter to Laurence Hope, 1 October 1947, Papers of Laurence Hope, Manuscripts Collection, National Library of Australia, MS 7216 Box 1 file 3A.

- Nolan and the Reeds first heard of Fraser Island from Englishman Tom Harrisson, a parachute instructor at the Fraser Commando School who wrote an article for Issue 7 of the Reed & Harris magazine Angry Penguins and who visited Heide in September 1944. In a letter to John Reed from Fraser Island dated 28 August 1947, Nolan enthuses about the island saying ‘no wonder Tom Harrisson felt for it’ (see Nancy Underhill, Nolan on Nolan, Viking, Melbourne, 2007, p. 138). A most interesting WW2 training film from the Fraser Commando School was made in colour, but unfortunately without audio, in January 1944 by Dr Frank Tate and affords a remarkable viewing of what the island must have been like just before Nolan’s visit. The film includes a clip of parachute training jumps into Lake McKenzie from 300 feet. At the 52 minute mark an instructor who has parachuted down with an inflatable rubber canoe, inflates and climbs into it and paddles away. He looks remarkably like Tom Harrisson. (At 59 minutes, Fraser Island fans can see the front mast of the Maheno being blown off as commandos of Z Force practice for Operation Jaywick.) Nolan could also have learned about Fraser Island and Mrs Fraser from Barrie Reid when Reid visited Heide with Laurie Hope over Christmas 1946. Indeed it is just possible that Urang Creek might not be Nolan’s first image of Eliza Fraser. Reference to an early painting known as Mrs Fraser and Bracefell can be found in Barrie Reid’s article on Nolan’s Queensland years (Art and Australia, Vol. 5 No. 2, op. cit., p. 447) where the work is dated ‘c. 1946’ and is said to be in a Melbourne private collection. Another reference is in T.G Rosenthal, Sidney Nolan, Thames & Hudson, London, 2002, p. 105, which states that the work ‘has been dated 1946’ and is still listed as ‘private collection Melb’. Mrs Fraser and Bracefell can be seen here. I suspect it could have been in the hands of the Reeds in 1967 because other paintings in their hands and listed in the 1967 Art and Australia Nolan issue all have photo credits from the same source – Latrobe Studios. Mrs Fraser and Bracefell seems atypical of any other of the 1947/8 Fraser Island genre – more magical, a lighter palette and with sparser vegetation. Perhaps the dating of this work as ‘c . 1946’ was well informed rather than, as appears on the face of it, to have been an error. Could it have been painted around Christmas 1946 during or soon after the Reid/Hope trip to Melbourne, and before Nolan had been to the Island? I think most likely not, in that the Eliza/convict theme is particularly well developed and at 4 ft x 3 ft, it is a relatively large work. Nancy Underhill has said ‘I can’t believe he painted this sort of narrative before he was in Brisbane. …. The size of the board suggests it was something he did not just toss off as a memory sketch…’ (Nancy Underhill, email to the author, 31 March 2012).

- John Curtis, The Shipwreck of the Stirling Castle, George Virtue, London, 1838.

- Henry Stuart Russell, The Genesis of Queensland, Turner & Henderson, Sydney, 1888.

- Robert Gibbings, John Graham (Convict), Faber and Faber, London, 1937.

- quoted in Kay Schaffer, In the Wake of First Contact, op. cit., p. 85.

- Henry Stuart Russell, The Genesis of Queensland, op. cit., p. 256-7.

- Robert Gibbings, John Graham (Convict), op. cit., p. 90-93.

- Robert Gibbings, John Graham (Convict), op. cit., p. 93. I am indebted to Michelle Helmrich of the University of Queensland Art Museum for first drawing this image to my attention.

- Elwyn Lynn, The Darkening Ecliptic, op. cit., p. 14.

- Robert Melville, Paradise Garden, op. cit., p. 7.

- Lesley Harding and Kendrah Morgan, Modern Love:The Lives of John & Sunday Reed, Meigunyah Press, Melbourne, 2015, pps. 52 and 185.

- Barrie Reid, Art and Australia, op. cit., p. 447.

- Nancy Underhill has observed ‘I agree the image in Gibbings is likely recollected in the Mrs. Fraser…Nolan’s mind-eye worked that way often when he did not consciously set out to,’ email to the author, 10 March 2011.

- Warwick Reeder, The Ned Kelly Paintings: Nolan at Heide 1946-47, Museum of Modern Art at Heide, 1967, p. 68.

- Sidney Nolan, Letters to John Reed after he left Heide on 8 July 1947, Papers of John & Sunday Reed, Australian Manuscripts Collection, State Library of Victoria, MS 13186, Box 2, File 6.

- There is no doubt that their relationship had reached a turning point and the letters from Nolan to John Reed make this quite clear. I believe his reasons for leaving Heide will be shown to be quite complex and more than just an escaping from what had become a difficult love triangle and from a muse who was becoming increasingly disquitening. I see an assertion of independence in his leaving (artistic, if not financial) and I like to imagine that his Watchtower Kelly painting, the very last of the first Kellys he painted and which was completed only a matter of weeks before he left Heide, is Nolan himself atop the tower looking out at the future; and to imagine that the naked figure walking from the sea in Fraser Island is not Norm the Forestry Commission foreman, but Nolan striding into that future in a new land. (Indeed, a bearded Nolan some years later bears some resemblance to the Fraser Island figure. This painting clearly had significance for Nolan – he repurchased it in the late 1960s giving it the circular provenance Nolan/Judith Wright/Charles Osborne/Bryan Robertson/Nolan.) But whatever the reasons, motives and emotions involved with his leaving, the letters make it clear that there was no animosity whilst he was in Queensland.

- Sidney Nolan, Letter to John Reed, 28 August 1947, op. cit.

- Sidney Nolan, Letter to John Reed, 25 August 1947, op. cit.

- Sidney Nolan, Letter to John Reed, 1 September 1947, op. cit.

- Sidney Nolan, Letter to John Reed, 15 September 1947, op. cit.

- Sidney Nolan, Letter to John Reed, 16 December 1947, op. cit.

- Barrett Reid, letter to Laurence Hope, dated ‘Monday’, posted Monday 29 December 1947.

- Sidney Nolan, Letter to Albert Tucker, Sydney, 19 January, 1948, published in Bert & Ned, op. cit., p. 75-77.

- Sidney Nolan, Letter to John Reed, 14 January 1948, op. cit.

- Sidney Nolan, Letter to John Reed, 3 February 1948, op. cit.

- Jane Clark, Sidney Nolan, Landscapes and Legends, a retrospective exhibition: 1937-1987, op. cit., p. 91.

- The marriage is mentioned by Nolan in a letter to Bert Tucker. See Sidney Nolan, Letter to Albert Tucker, Sydney, 19 April, (1948), published in Bert & Ned,op. cit., p. 81-82.

- Robertson had written to Sunday Reed on 11 January 1957 stating ‘Nolan tells me he left on loan with you the entire output of his work up until 1948.’ John Reed replied to Nolan saying ‘the position with regard to your early paintings cannot be resolved in terms of “loans” – they were certainly never “borrowed” ‘. See John Reed, letter to Sidney Nolan, 29 January 1957, included in Letters of John Reed, Ed. Barrett Reid and Nancy Underhill, Viking, Melbourne, 2001, p. 514. .

- With readings by Shelton Lea, the book was launched by Alex Miller – this appointment at Heide with the ghosts of Nolan, Sunday and Barrie Reid presaging his Autumn Laing by some 16 years.

- Photocopy of the mock-up, a gift from Shelton Lea, in possession of the author.

- Elwyn Lynn, “The Illuminating Ecliptic” in The Darkening Ecliptic, op. cit., note 2 on p. 21.

6 Comments

Join the conversation and post a comment.

A fascinating and forensic examination of a key painting in Nolan’s oeuvre.

David this is incredibly thorough and scholarly. Fascinating material. well done! betty

sorry about the typo in my last name.

betty snowden

again, brilliant work David.

Thank you for this publication. I regularly guide this work as a Volunteer Guide at the Queensland Art Gallery. It is most helpful to have more insight into this significant interpretation and representation of a very sad event in our history for Australian Aboriginals living on Fraser Island whose help was so misinterpreted in such a superior way casting a negative shadow on the 1st Nation People’s survival in thier own country.

Thank you for your research, analysis and writing about Sidney Nolan and his Fraser Island paintings, and particularly Nolan’s strange, intriguing painting, ‘Mrs Fraser.’

All these conflicting images and stories about Mrs Fraser, I wonder what was true. One thing is certain is that she was an extraordinary woman, great strength and a survivor.

Where you have quoted Nolan’s impressions when he was there on Fraser Island, I know what he meant because when I first visited the island on a day trip many years ago, I felt the presence of the missing (removed) aboriginal inhabitants, a sorrowful yet serene sense.

Thank you Lynn for those comments. It’s nice to know that 9 years on, my research and interest in Nolan’s Fraser Island works still finds its audience!

A new, quite major exhibition on Nolan and including these paintings will be installed later this year at Heide Museum of Modern Art. “Sidney Nolan: Search for Paradise” is scheduled to open 31 October and will examine one of the artist’s deepest impulses and the journey of self-discovery it engendered.