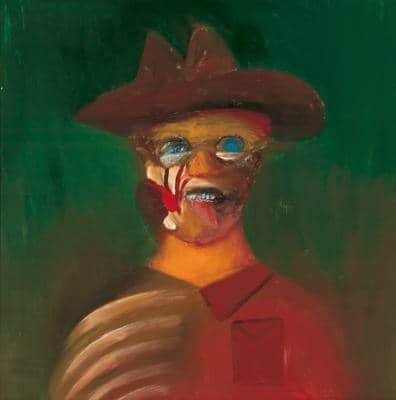

Interviewed endlessly, Sidney Nolan became the consumate interviewee. Apparently relaxed and in his element, he deftly handled questions to reveal as much or as little of himself as he chose, or to cast on events and people alike the emphasis he wished. Listening to the tapes, reading the transcripts – it is he who sets the pace, the interviewer who follows. This trend is much less evident in a late interview with Michael Heyward in May 1991 just eighteen months before he died – perhaps he was less cautious when not being quizzed about his paintings or his past. We hear him speak of the Ern Malley poems and of his own role in the furore of their publication. The interview supports a contention that Malley was as much an alter ego for Nolan as was Kelly.1 Indeed his 1969 portrait of Malley can be seen as a most realistic self portrait, with the verso carrying in his hand writing the Malley quotation ‘What would you have me do, go to the wars?’

Sidney Nolan, Portrait of Ern Malley, 1969

More than this, we hear his passing thoughts on a wide range of subjects. On Whitlam: “Whitlam wants me to paint the whole thing of the Dismissal ….and I said ‘OK I will – when you come clean’ …. he won’t quite come clean and I can guess why too, because once again it’s the CIA involvement.” On politics: “I was never a communist, and I’d never joined up and I’d never voted – well I’ve never voted in my life – but I was always a believer in the heightened consciousness of the proletariat, well, I feel it still of course.” On being fatalistic: “She [Sunday Reed] was fatalist in a kind of bourgeois way, I was fatalist from a proletarian point of view.” On Australia: “Whitlam was in power and Australia was going to be different …. Whitlam was in full flower and everything was possible .… And now I think …. that whatever happens it’s going to be too late for the Australians. You see, whatever they do they’re too late.’

And 50 years on, we also have some deeply personal and apparently unguarded reflections on his relationship with John and Sunday Reed: “She could never see the logic of why I left. I couldn’t see the logic of – well I didn’t want to go either – but I couldn’t see the logic of staying [pause] but she wanted it both ways you see, she wanted [pause] [unclear] and so did John. Everyone wanted something that was impossible, which is natural for human beings [pause] but they don’t usually get it.”

Sidney Nolan, Interviewed by Michael Heyward, London, 5 April 19912

Sidney Nolan: ….. up to Cork Street for a 4 o’clock meeting.

Michael Heyward: Can you remember when you first read the poems, the first time you saw them?

SN: Yes

MH: How was that?

SN: Well, I don’t know whether I was an editor at that point, although I suppose I was.

MH: I think you were.

SN: Yes

MH: Harris sent them across saying “see what you think” – this was to John Reed – saying “see what you think of these” and he showed them to you.

SN: Yes, and I took them away. I thought they were the product of somebody who’d been in Europe, that was my first feeling, that they weren’t home grown.

MH: This was before you knew anything about ….

SN: Yes, when I was first handed the typescript. I thought they were a bit curious in their, sort of, internationalism in a way … Seeing that Ern Malley had never been abroad according to his sister’s story, I thought that didn’t quite marry up, and I said so,.

MH: Do you remember that it was some suspicion that you and Sunday Reed had that Kershaw3

might have written them. Do you remember that?

SN: Yes, that was more her idea than mine, because I knew his work and didn’t think he’d written it. He wrote The Denunciad … I didn’t think it was quite him, although it could have been. I thought it was someone who had lived abroad, some Australian who’d been abroad and come back and was writing in this way. Since that didn’t tie up with what the sister said, I just had to take it for granted that he hadn’t been abroad and that he’d picked up the books. I had kind of reservations about the poems which I said at the time. I didn’t quite see how an Australian, born and bred in Australia, and died in Australia, actually could have written them, but nonetheless I accepted that was the case. But I had this edgy feeling that these references were so sophisticated, this Shakespeare stuff I suppose

MH: Yes, well there’s lots of .. there’s references to Mallarme, to Marlowe, there’s lots of European poetry…

SN: Yes, but that was due to my innocence a bit because I should have known about Brennan and Mallarme. You see I actually didn’t know quite a lot.

MH: Of course McAuley did know all that. In fact until quite late in his life… I think McAuley finally came to acknowledge that Brennan wasn’t the bees knees, but he admired Brennan a lot.

SN: Well culturally he was very remarkable.

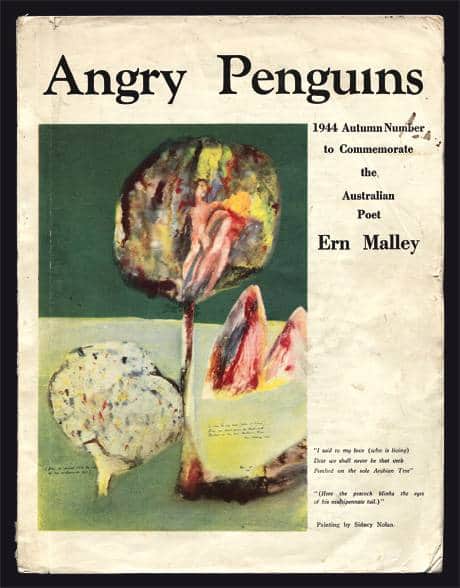

MH: And then the Ern Malley painting you did up in the Wimmera when you took the poems up there …

SN: I did that in Nhill … the figures in the tree … yes, well that was fairly autobiographical in a way. As much as Ern Malley it was a sort of private thing …

Sidney Nolan, Arabian Tree, 1943

Cover of Angry Penguins, No 6, June 1944

MH: How was it autobiographical?

SN: Oh, that “dear we shall never be that verb perched on the sole Arabian Tree”… and my life was such at the time that that was rather true of me and I guessed that I in fact would never be that bird perched on the sole Arabian Tree … (chuckles). My life was not going to work out, so the painting – which I return to of course in other versions – is a bit to do with these isolated figures in the tree. We were very fond of each other, but isolated, and down at the right of the tree you will remember there were three sort of rocks, three pinnacles of rock, which are actually the end rocks of the Grampian Mountains, three peaks which are up at Horsham. And I had a friend, Douglas Cairns, [..unclear..], he was an apple grower down on the Mornington Peninsula, or was it [..unclear..], and he said they were love fruits. He was a very good letter writer and used to write to me a lot, and he wrote saying those three shapes were kind of love fruits. So in a way the painting was rather private …[long pause] .. but triggered off by that sort of tragic sort of thing, that we shall …[long pause] .. that it wouldn’t work out, you know, that it was a dream that wouldn’t come true …[long pause] .. which was roughly speaking my life at the time …[long pause] … which was the personal thing which was mixed up with Heidelberg and all the rest of it.

MH: And you were very … and you knew Rimbaud?

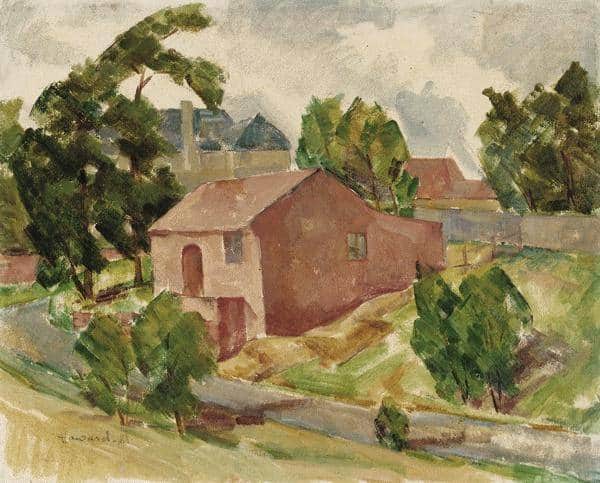

SN: Yes, well I’d worked with Sunday Reed on all that. But independently of her I’d been, you know, I’d been quite mixed up with it when I was very young. I was introduced to it by an artist and painter called Howard Matthews

MH: who’s very well known [ unclear – could be “who’s not well known”]

Howard Matthews, House at Clifton Hill, private collection.

SN: Yes, he was a very good painter. He’s now dead. He was at the National Gallery Art School and he showed me these poems which I think were actually translated by Edgell Rickword and they were up in the library, that big circular thing, where I read every night. So I didn’t draw very much when I came, I just read. I’d spend hours .. Neitzsche, Mallarme. And I read Rimbaud there. So I was heavily into that and in 39 or something I produced that abstract head for the Contemporary Art Society which I’ll be showing in an exhibition I think on my birthday next year in Melbourne. I’m having an exhibition of completely abstract work which I’m now doing, lots of it, and trying to tie it up with early abstract work. So I was very interested in Rimbaud. Yes.

Sidney Nolan, Head of Rimbaud, 1938-39, Heide Museum of Modern Art

MH: Is there a connection between Malley and Rimbaud and Malley?

SN: Yes, very much. Well in their lives really.

MH: The outsider and …

SN: Yes.

MH: And did you see yourself as an outsider?

SN: Oh yeah. Oh yes, I was … Yes, there is a proletariat. As a worker, as a son of a worker, going to a factory at age 14, I was fully conscious of being an outsider, because that’s what you are.

MH: And like Malley, you’d educated yourself. There’s a letter in the… I had a look at the Reed papers which are in the Latrobe library in Melbourne, and there’s a letter you wrote to Malcolm Good which says exactly this sort of thing about …

SN: Yes, well he was a communist ..

MH: … and with the letters, he was trying to take the antiseptic communist line ..

SN: Well, although I was never a communist, and I’d never joined up and I’d never voted – well I’ve never voted in my life – but I was always a believer in the heightened consciousness of the proletariat, well, I feel it still of course. You know, because, what else?

MH: The letters are also a defence of the freedom to think for yourself and not to have to follow the party strictures which seem at that time in Melbourne to have been fairly Stalinist.

SN: Well, there were various complicated things to do with Josl Bergner and Noel Counihan and Harry de Hartog. But anyway, I never became a communist but I always believed in that the freedom in society would have to come from bottom up, rather than from the top down. Well even after this last episode we’ve just had, I still feel the same thing.

MH: Which episode?

SN: The one in the Gulf. You see that’s imposition from the top down, supposedly for the good of the many, but of course that actually doesn’t quite work out.

MH: No and it’s now catastrophic ..

SN: It’s now of course interfered with a very delicate dangerous balance, it’s upset it. Now it’s up for grabs.

MH: It’s been a disaster … Can you remember how you felt, your reaction, when the news came through that the poems were a hoax? It must have been a …

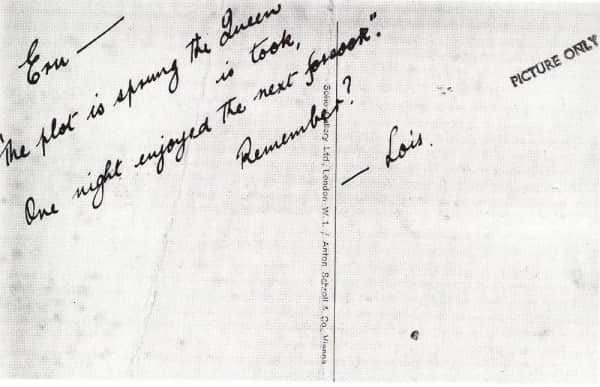

SN: No, I had no interest really in that .. I mean I was interested as a drama, but I didn’t think it made the slightest difference to the poetry. I thought that was the .. you know, the plot thickens and all that sort of thing, but whatever is in the poems, the sniping, the postcard … “the queen forsook” whatever4 …

MH: yes … one night .. I’ve forgotten it … one night … the next .. forsook.. the plot is .. something

Postcard pinned to Ern Malley’s wall, verso

SN: yes, well it’s as Meredith said: “Passions spin the plot”.

MH: It comes from Purcell

SN: Yes, it’s Purcell.

MH: Max Harris thinks it’s Shakespeare

SN: Yeah, I know he does, yes. Well, Max is …. If you come from Adelaide [both laugh] .. that happens a little bit, I guess it’s passé. No I just took it for granted that that was part of the drama, made not the slightest difference to the poems.

MH: And the Reeds. Did it change the way they thought about … Did either John or Sunday?

SN: Well I think John had a different idea from Sunday in a way. He then went into a kind of political thing in which he got all the academics to contribute, the pros and the cons, seeing he was a lawyer he wanted to see both sides put.5 But I had no interest in that.

MH: In that kind of polemical defence …

SN: No, I mean I sort of kind of proof read it all and dealt with it all. But I wasn’t interested in Dorothy Green saying this or ….

MH: To you it was all more private and more intimate

SN: Yes

MH: Yes, I can see that ..

SN: And if that’s the way they chose to do it, that was OK by me. You know it’s a bit like saying Rimbaud’s sister wrote his poems. If she did, well that’s OK. It just doesn’t make any difference ..

MH: Or that Bacon wrote Shakespeare

SN: Or that Bacon wrote Shakespeare. You see, if he did, well then good luck to him

MH: And what did Sunday think of the poems?

SN: Well she thought they were very good. But I think that she, a bit like me in a sense, but more than me, she thought they were connected with our own private life; that’s why the figures in the tree – herself, myself … she kind of took it for granted that something like this would happen to something like us

MH: She was a fatalist?

SN: Yes, I mean I was too; but in a quite different way. She was fatalist in a kind of bourgeois way, I was fatalist from a proletarian point of view. ..

MH: And of course there is that fatalism in the poems

SN: And there is the fatalism in the poems about the war “there’s deceit in these shell holes”

MH: That’s right and a very literal kind of fatalism about his own death which I think is what seduced Harris more than anything else .. a very romantic fulfilment of this kind of .. because he’s just published D B Kerr, one of his friends that were killed …

SN: Yes, he was an airman

MH: … in New Guinea and I think Harris thought this was another figure in ..

SN: But I think Max had a more literary point of view than Sunday or myself had. See we had a very personal point of view

MH: and a polemical point of view too. It seems to me it did him a lot of damage.

SN: Well, he took it very seriously, the results of it. You see John Reed and Reg Ellery and Max went over to Adelaide to hear the court case. Sunday and I stayed behind and I think we thought it was irrelevant, although of course in practical terms it was very serious since he was fined … it was no joke. But Sunday and myself, and myself in particular I suppose, Sunday thought that all that was irrelevant.

MH: You’d left the army by then hadn’t you?

SN: Under dubious circumstances! Yes

MH: Do you think there was any connection in your mind between the way of you leaving the army and when you had the other identity and Malley who was another identity too? Did that kind of thing … do you see what I’m saying?

SN: Yes sure I do. But I just took it for granted that these kind of things could happen, that you could change your identity according to circumstances, or to necessity, or to a fatalistic way, or whatever. Or what was your identity, or who did it belong to? Did it belong to the Australian Army, or did it belong to poetry, or did it belong to your father and mother, or did it belong to this or that or … ? So it was very fluid, a bit like Ford Maddox Ford. It’s very difficult to pin down a question of identity.

MH: Especially tied up with a time of war

SN: Well you see, in the Malley poems, this business about war: “there’s deceit in these shell holes” … I’ve forgotten the rest.

MH : I also remember the great portrait of Ern Malley which you did in the early 70s and you attached the epigraph from Malley “What would you have me do? Go to the wars?” And that seemed to me to go back to those days …

Sidney Nolan, Ern Malley 1973, Art Gallery of South Australia

SN: Well it’s a kind of Australian digger isn’t it?

MH: … and when you decided not to go to the wars?

SN: I didn’t think it was wrong to go to the wars, and lots of my friends went to the wars. I had no protest against the war on the grounds of being a conscientious objector or anything like that, but I just wasn’t interested whether the Japanese came or whether they didn’t come; so if they didn’t come now they’d come in 50 years time. From my point of view, personally, I just wasn’t interested and I’m still not. ‘Cause they would, they did .. and there’ll be Indonesians and the rest of it (unclear) .. They will, and as a result of this Gulf thing they’ll come a fraction quicker…

MH: I think that’s probably true

SN: Oh yeah, the whole push and swing .. but that is where the so-called heightened consciousness of the proletariat came from, is that you made up your own mind about all questions of destiny, fate …

MH: And your own identity

SN: and your own identity, wars, nationhood. Whatever it was, your heightened perception so-called which you’ve got as a birth right from not being educated or born into a structured society gave you the insight and the rights or the freedom to do what you thought fit.

MH: I think that’s especially Australian, when people do make themself up from scratch because they have to. You can be born into certain parts of English or European or American society and you don’t have any choice, but in Australia …

SN: Well there were plans for me to go to Oxford as I had a rich uncle and aunt and my father kind of sent me over to them. And I was going to go to Oxford, but my aunt died so I didn’t in the end go to Oxford. If I’d gone through that whole process, if I’d done a kind of Patrick White job, and I’d gone through the whole thing, gone through Cambridge and all the rest of it – which of course I’d dearly wanted to do and I still wish I had’ve done – but I prize my own freedom even more than the assets that I would’ve got – at least I think I do, I’m not too sure .. I rather envy people who go to University. You’re 25 before you come out and that’s a third of your life spent .. not working in a factory with fumes and steam and [unclear] and noise … and all the rest of it. But on balance I’d still rather have it the way I had it. So in a sense I associated Ern Malley with the proletariat even though some of the statements in the poem of course are very right wing.

MH: Yes. Well he’s really all over the place. There’s quite satirical remarks about the left wing. They’re coming from McAuley.

SN: Well that’s a joke – they’re slightly sinister. I mean “the popular back to front”, well that’s no joke, that’s the Goebbels stuff, that’s quite serious.

MH: McAuley’s so complicated because until a year or two before that – he was never a communist either – but he was very sympathetic to the left and that was his position until he was called up and then he went into the army and his politics turned around quite quickly.

SN: Somewhat like Rupert Murdoch

MH: Somewhat like Rupert Murdoch

SN: Well, all you can say to that sort of thing is that they’re lost to the fold. You see in all the obituaries of Graham Greene they refer to his continued friendship with Philby. He wrote of course the foreward to Philby’s book and people wonder why he persisted in it. Well I just read that when he was an agent, MI5 and the Secret Service rather, that’s Graham Green, well his minder was Philby. Graham Greene didn’t know at that point that Philby was a Soviet agent, but he was friendly with him all his life and when he was asked why he said, “Well you know, he served his own cause, would you say he was any worse than Reagan?” – or any better if it comes to that – well he was still made OM wasn’t he? The Queen must have been totally aware of his position … and also aware of mine. So it makes it interesting, it makes England quite an interesting place in spite of its defects. Mmm .. I’ve rather departed from ….

MH: Can you remember whether Sunday had any measurable reaction to her discovery that the poems were a hoax? Or she thought like you that it didn’t matter how the poems came to be?

SN: She saw it like me. She just … we were … In our sort of situation we weren’t terribly interested in the court case – or even though John Reed had gone over taking Reg Ellery over as an expert witness and he wasn’t called – but we just had this kind of fatalism – that’s the way it was. That’s what the poems had said anyway, hadn’t they …. Something like that?

MH: They had – it’s almost as if the poems in some way predict …

SN: And seeing our own lives were kind of doomed, the kind of lesser doom of a court case didn’t loom very large.

MH: Ern Malley’s been with you all the time, but in that sense of doom, you’ve outlived him haven’t you? I mean the doom didn’t – or did it? – come to pass

SN: No, it didn’t actually, no. I mean the aspirations .. tho I must be careful to watch the Faustian kind of position … [they look at poems]. You see they confessed that was a good poem didn’t they?

MH: Yep, they called it a “come on”. That’s a very good poem6

SN: It’s a lovely poem, yes.

MH: The last four lines are just ravishing

SN: It’s marvellous. Yes, yes, I think so.

MH: I’ve an idea that that was McAuley’s, that he already had written it and that they dug it out …

SN: I think so

MH: …made a change or two – but the poem already existed.

SN: I think it’s McAuley’s poem but I think that some of the rhymes have been …

MH: I think it’s very interesting here that Stewart, through the music …

SN: yeah, well I can ..er [long pause] .. well you see these guys were [unclear] .. they were very smart rhymes … elipse, eclipse; chien, to seen;

MH: they do this very very often, it takes quite a lot of skill to do it, they rhyme a monosyllable with a polysyllable very often. This is the one according to Stewart where they used the Rhyming Dictionary ..

SN: disaster, alabaster .. well they could have, yeah – wraith, faith ..

Ripman’s Dictionary of English Rhymes

MH: He gave me the Rhyming Dictionary that they used, and it seems to fit. [long pause]. The other thing, you also talked when John Thompson made the ABC programme about Ern Malley, about the gentle eroticism and I think that’s very interesting too

SN: And I said it didn’t exist in Australia

MH: That’s right and I think that’s true, and I think that ties up with .. you say that it’s maybe an oriental thing but it ties up with

SN: No .. I didn’t say that – well perhaps I did, perhaps I did. Did I? Yes I did, I did say that.

MH: Yes, well it ties up with what is a new note in Australian poetry. I don’t think there had been anything like that before.

SN: No there hasn’t been

MH: Perhaps that’s all .. you know the prosecution of Harris seems to have been really a horrible, nasty small town affair.

SN: Yes. The sergeant saying they went into the park …

MH: Yes, well maybe even their dull minds were affronted by the sexuality of the poetry because ..

SN: Yes, there it is there, it’s “Night Piece”

MH: Well the poems are more about sex than I think anybody has ever said.

SN: yes. Well that’s where the actual rhymes are so nice. [quotes from poetry – very unclear}. That’s worthy of Larkin or Auden or anyone isn’t it?

MH: Yes, very clever.

SN: What I was going to say earlier which you asked me and I didn’t quite answer was that my own life ended up all rather free of all this … you see at the end of my life I find that I’ve survived all this. I’ve even survived the sort of fatalism of it all. But I’ve paid a heavy price … I’ve lived a very sort of mixed-up life. But in the end it’s worked out, whereas in the end for him it didn’t work out.

MH: For Malley?

SN: No.

MH: and when you read the poems …

SN: Nor for any of the people that I was associated with with Ern Malley – Max Harris, Sunday Reed or John Reed. All was broken up, or lost, or ..

MH: And it worked out for McAuley and Stewart, after a fashion, but they paid a price

SN: yes, they paid a price.

MH: But when you .. at the time, in 43 or 4 when you were, almost as it were, living out the poems to some extent, you couldn’t see a way out at all

SN: No, I couldn’t then, no.

MH: I can understand that

SN: No, I thought that would be my destiny like his …

MH: Perhaps that’s one meaning of the hoax, that .. which is what we talked about earlier, that for Ern Malley there did turn out to be a way out. He didn’t exist

SN: yeah, well that’s a very er .. well, they actually of course spell it out “I have split the infinitive” and “Beyond is anything” … and “Spain weeps in the gutters of Footscray, Guernica is the ticking of a clock” and “the nightmare has become real. Not as belief but in the scrub typhus of Mubo” Well that’s very Australian isn’t it, only an Australian actually pick up the [unclear] of Mubo

MH: And that dates the poems very exactly, and this reference to Spain and Guenica also

SN: And “I have heard them shout in the streets, the chiliasms of the socialist Reich” .. well that’s pretty tough stuff. See I didn’t like that much, and that’s why I thought it must have been someone who’d been in Europe who’d … not only stylistically, but someone who’d experienced the whole thing politically. Because that, really, of course is what’s now being said in the newspapers “the chiliasms” – they don’t put it as concisely as that – “the chiliasms of the socialist Reich” – that’s what’s going on with the whole breakup of Russia, which may be isn’t to anyone’s advantage in the end, maybe it is, maybe it isn’t.

MH: It’s like the situation in Iraq

SN: Yes, well you do one thing, you push one way, and

MH: Yes, that’s what the Americans never understood .. they never understood that at all.

SN: Such a volatile place you see. So … you know Kurdistan was strung across four countries and then it was arbitrarily divided by Churchill you see. Churchill did the bit on Iraq. He was the one who drew the maps in Iraq. And this is all very delicate because the people speak different languages, they’re different races

MH: They’re different kind of Muslims

SN: Different kinds of Muslims, yes. And suddenly you chop them up and put them here and put them there as they did in Africa. Well, now we’re getting the kind of read out and if you put a kind of stick in a hornets nest this is what you’re going to get, and that’s what we’ve got.

MH: That’s right

SN: “Spain weeps in the gutters of Footscray” … that’s a very good line.

MH: yes

SN: “Spain weeps in the gutters of Footscray” … you see that is, in a sense, is in contrast to “chiliasms of the socialist Reich” you know … “Guernica is the ticking of a clock”, that seems to be a sympathetic reference ..

MH: That’s quite true

SN: .. whereas that seems to be an unsympathetic

MH: That’s right he’s all over the place. He’s …

SN: That’s an unsympathetic reference. Well, they can’t be blamed, it was so early in the piece. But I thought politically this was rather true, and of course this is the part I illustrated. “I said to my love (who is living)” … and of course there’s a bit of TS Eliot at the end “sad at his own funeral” … that’s what I did … “dear, we shall never be that verb perched on the sole Arabian Tree” … well, that was my life and I took it in the Shakespearian sense that that was my destiny that I would never … [very long pause] … and of course that was the case with Sunday also, she knew that we would never .. [long pause] .. never be that bird perched in the sole Arabian tree… we both thought it .. [pause] .. but that’s not much fun. So the poem was very much to do with our own lives .. [pause] .. and seeing that this had a tragic outcome, at least seeing that the poetry was tragic …

MH: Particularly that one

SN: Which is that.. Petit Testament, ah that’s like Rimbaud … [reads, barely audibly] … “In this twenty fifth year of my age” .. [pause] .. and as it turned out our own lives did of course have a tragic outcome … but we kind of, we kind of knew in some way … so we had a very intimate relationship with the poems

MH: What triggered Ern Malley in the early 70s when you did the series of paintings which are now in the South Australian gallery?

SN: That’s a kind of didactic thing to show the logic that’s behind and that works through all this. I illustrated ever four lines whatever it was with drawings and tried to show that it did make sense, by doing a drawing of each four lines – and feeding into it some of my own lines to make another kind of point – but to try and prove to McAuley and Stewart that the thing did have a logic in it and a meaning like other forms of poetry and that it wasn’t nonsense. And I’m going to do it again, now that I hear about Evatt, because I can see another way of coming in on this…. Because I ..

MH: well they pulled back at the last minute from doing that, that was an idea ..

SN: Yes, well it would have been very good to have done so actually, it would have been sensational

MH: They didn’t bring [unclear] …

SN: You see, the only thing I feel, to put it very simply: if there is no deceit in the poetry; there is no deceit in the hoax either. I think it’s fair enough… I think the hoax is OK .. it probably makes Harris and myself, but probably Max in particular, deserved some sort of push on him perhaps.

MH: Well whether he deserved it, he was sitting pretty

SN: He was sitting pretty, but he didn’t deserve it. I shouldn’t say that because I just ..

MH: He never had a chance

SN: He never had a chance. No, he was sitting pretty and he writes this thing up in the same position as Max Brod, faced with the papers, on Kafka. But I think the only mistake they made was to insist that it was nonsense. You see if they hadn’t done that it wouldn’t have persisted

MH: Stewart even talked about this a little bit. When the hoax was exposed it wasn’t … Stewart had told this woman in Sydney called Tess van Sommers, who was a journalist, a trainee journalist, he told her and I think a few other people might have known too in Sydney … he told her that they’d done the hoax, that Harris was being hoaxed, and that when the story blew she could write it up. McAuley didn’t know about this, and she was in Sydney one day and she saw Angry Penguins on sale and she realised that this was Ern Malley and she went and told the newspaper, and that was the Sydney Sun and Colin Simpson worked for Fact …

SN: Oh yes, I remember that

MH … Fact, which was the supplement. But McAuley in particular was furious. He didn’t ever want the hoax to be exposed so soon. And they weren’t ready for it, they hadn’t … that statement which has become now very famous and was published in Fact, they wrote that, there were two drafts of that and I’ve seen both of them, McAuley wrote one and Stewart wrote one and they were cobbled together … they were written at speed over a weekend. I think they were written under some pressure to justify …

SN: Well they’re false, apart from anything else .. Do you think that that was written in one afternoon? I mean, how could it be?

MH: I don’t know. I mean …

SN: Well I do know, because you know I’ve got concordances and rhyming dictionaries and all sorts of things around the place. You couldn’t do all of the Ern Malley poems on one Saturday afternoon in the barracks

MH: About eight hours they say. That was what Stewart said

SN: I’d do a lot to believe it

MH: I mean that’s pretty quick. But I’ve talked to other poets who say you know, you could do it. .. you could do it.

SN: [unclear name] and Les Murray wouldn’t say you could do it

MH: No no, in America I’ve talked to ..

SN: You couldn’t

MH: I’ve looked hard for evidence, I’ve talked to people, cause I was suspicious of it.

SN: It’s taken them weeks

MH: Suspicious of it. See everything starts to shift. It’s hard to know …

SN: But how are you going to get these rhymes in one afternoon?

MH: Well you sit there with a Rhyming dictionary …

SN: .. but they’re so delicate. You can’t get those out of a Rhyming Dictionary.

MH: I mean in one way it doesn’t matter, it doesn’t matter ..

SN: No, no, no, it doesn’t matter, it reads just as well

MH: .. whether it took them a month or it took them an afternoon. But my suspicion is that this poem already existed – that the first one already existed.

SN: I think he’d had a postcard of Innsbruck and I think he wrote the poem on the postcard alright and I think it already existed. Yes, I suspect ..

MH: I talked to this bloke in Sydney called Alan Crawford who was at the University with McAuley and he said that ‘I can remember when I read the poems’. He was the bloke that told me about Evatt. He said he saw McAuley in Melbourne soon after and McAuley said to him we almost got Evatt.

SN: .. we almost got Evatt.

MH: But he told me that when he read Ern Malley he thought he could see lines from drafts of McAuley’s poems that he’d already seen, and I said can you show me which ones but he couldn’t remember. It’s so long ago.

SN: Yeah I had something in my mind I was going to say about ..

MH: Sorry

SN: That’s alright. .. about Evatt. Ah yes, Whitlam wants me to paint the whole thing of the dismissal, because I know most of the people and you know I used to see Ellicott and a bunch of them and he’d say why … But I used to see him and we used to talk, but then I knew Whitlam very well and I knew lots of other people, and Whitlam says, said to me “Why don’t you paint it” and I said “OK I will – when you come clean” …. [SN musing] … because he won’t quite come clean and I can guess why too, ‘cause once again it’s the CIA involvement …

Dismissal of the Whitlam Government, 11 November 1975, Vice-Regal press release

MH: He denied it

SN: .. which he denies, but nothing’s very clear and that’s the way it went. Otherwise you have to pitch in the reserve rights of the Crown and all that sort of thing. You know, ask the simple question whether the Queen’s representative possesses more power than the Queen and you have all these .. er .. awkward [unclear]

MH: I mean Kerr probably did make those connections in America. I don’t think Conlon7

was in on any of that though.

SN: No no, I don’t think so, no. No, Conlon went off to be a doctor … he disappointed, he was sad, and all that sort of thing.

MH: Conlon published Reg Ellery’s, helped to get published, Reg Ellery’s … was it the autobiography soon after Ellery died.

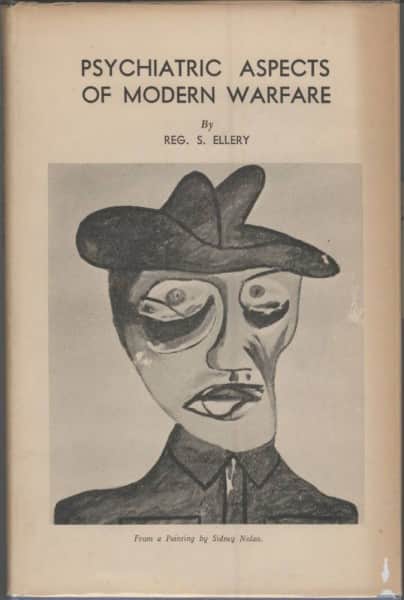

SN: That’s right. Well we of course had published Reg Ellery: The Psychiatric Aspects of Modern Warfare .. reminds me of the soldier’s head on [unclear]

Sidney Nolan, Head of Soldier, 1942

Cover for Reg. S. Ellery, Psychiatric Aspects of Modern Warfare, Reed & Harris, Melbourne, 1945

MH: That’s right. And that’s … he comes back in Ern Malley doesn’t he?

SN: Mmnn … the same thing. I turned it into an Australian soldier with one side of the face missing ..

MH: That’s right, with the tongue

SN: .. and the tongue hanging out and the eyes [unclear – perhaps ‘bare’]

MH: So when Ern Malley comes out in 73, that’s remembering

SN: mmnn. Yes, well now with the Gulf thing I think I’ll have another go … CIA, Kerr, Evatt, Whitlam, everybody else

MH: So you’ll paint the dismissal

SN: So I’ll paint the dismissal … I don’t feel like doing it I must say [chuckles], I don’t know if I’ll be able, but it’s there to be done

MH: It is there to be done, it’s true. Did you ever meet Stewart or McAuley?

SN: I met McAuley once, briefly. It was only very briefly, just to say hello to. I never met Stewart at all. McAuley only for five minutes, so we never talked about it. Of course, the problem is, why are we all at it now?

MH: At Ern Malley?

SN: Yes, with the reference to Evatt, prepared to hop in again, seeing another angle on it all. Well in fact leading through to Kerr and the dismissal. Well, that’s deceit, and all the rest of it. There’s a connection and being …

MH: I don’t think Evatt ever knew that he was almost … well, maybe he did. I mean he certainly would’ve read the poems wouldn’t he, after they were published?

SN: yeah, yeah. But all I need is a clue and of course then I can work. I wont say … ‘cause I’m the opposite of what I seem to be I suppose. Once I have a logical progression I can work, whereas it seems the reverse, that I work in a kind of Illogical way, but first of all I have to have the logic and then I can work.

MH: But wasn’t a specific trigger in the early 70s that produced … there wasn’t one thing that happened or that made you think that right now’s the time to do Ern Malley?

SN: [very long pause] … er … I think it was something to do with the fact that Whitlam was in power and that Australia was going to be different, because I took them all out to South Australia. I did an enormous amount of stuff, it’s all in Adelaide. And I gave it to them because they were going to build a special gallery for it, and Whitlam was in full flower and everything was possible, and Lanyon was going to happen … So I think it was at the thought of a kind of flowering of Australia that I returned to this, to all the Ern Malley stuff … And now I think I’ll return to it again on the complicated basis that whatever happens it’s going to be too late for the Australians. You see, whatever they do they’re too late.

MH: That was the chance

SN: Well there were various chances during the war. There were chances there, there were chances with Whitlam, there were chances again with Hawke and everything else, the boom in the 80s with entrepreneurs in Perth and all that sort of thing ..

MH: Bond

SN: And now it’s come round that the whole thing is halted. The whole Muslim thing’s activated Indonesia, the Japanese have the third biggest defence budget in the world ..

MH: They do

SN: So these are all very clear signs that the game’s beginning again and Australia’s tucked away [unclear] … I mean I’d love to see it come out on top as the prince of the princes, but it’s not going to be quite like that is it?

MH: No, no it’s not. I wanted to show you these …

SN: Sure. I’ve still got to watch my time …

MH: Well it’s 3.30 now

SN: That’s all right, we’ve got another five minutes before I go.

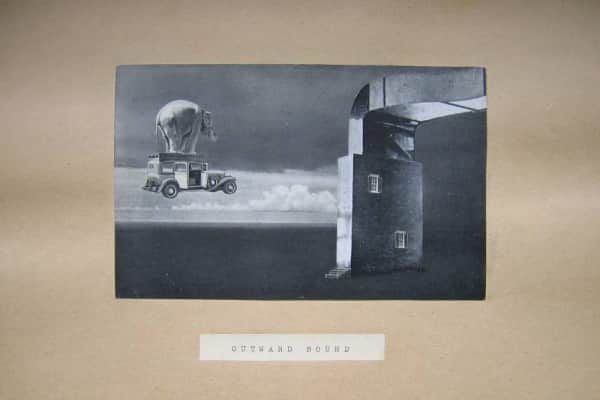

MH: Harold Stewart had also done these collages which were to be Ern Malley’s – these are not very good photocopies – which were to be Ern Malley’s art work. He cut them out of the National Geographic and pasted up these ..

SN: I’ve just got this book there of ..

MH: Max Ernst, these derive I think from Ernst

SN: Yeah, I think so. I just ..

MH: That’s a good book that. I’ve only seen that in the German, it’s just come out now in English

SN: Yes, I’ve just bought it. I haven’t looked at it yet. But you see that’s Max Ernst there .. in a way. That’s quite good

MH: These were … they’re not bad … these were never sent to Harris because the hoax blew up.

SN: “Outward Bound” .. very good.

Harold Stewart, Outward Bound, 1944

MH: These were done only by Stewart

SN: Yes, well they’re quite good. They’re like that guy I saw a program on the other night. Not Hirschfield, the German chap who changed his name to an English name … Heartfield

MH: Heartfield yes, and Hannah Hoch. Yeah, they’re quite like Heartfield

SN: Yeah, they’re quite like Heartfield. It was a programme which was of course anti Nazi stuff. The problem one has to think about is whether these two people were right wing or whatever it might be. Obviously by the look of these Stewart was less right wing than ..

MH: Stewart’s apolitical.

SN: less right wing, apolitical, than McAuley. I think they’re quite interesting. Can I get copies of these do you think somehow?

MH: I’ll send you some

SN: Will you send me some? You know having been down to the Antarctic and all that I sort of see what he was about.

MH: I’m going to … Stewart’s given me permission to publish them in the book

SN: Yeah, well ..

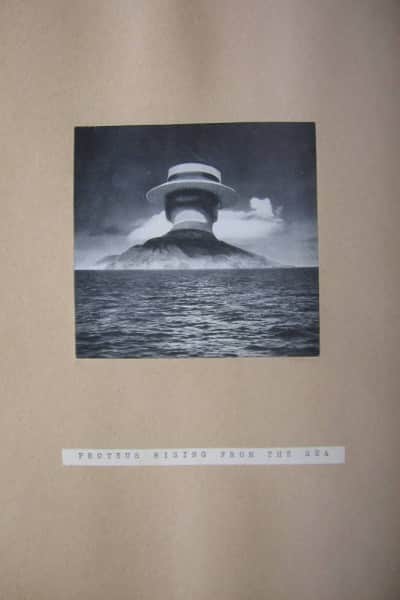

MH: See I think that one’s … that’s Ern Malley I reckon

SN: Yes, that’s pretty good isn’t it? “Proteus Rising from the Sea”

Harold Stewart, Proteus Rising from the Sea, 1944

MH: It’s in fact an island in the West Indies

SN: Yes, what Proteus is?

MH: well, he’s cut the boater from … but you see, like Ernst’s collages they’re done meticulously. I had to go and get them from his sister in Sydney, and I was only allowed to have them a short time, and I got them photographed and I gave them back.

SN: Well I will actually be having this exhibition next year on my birthday in Melbourne, and a whole lot of collages right back to 1939

MH: I’ve seen them, I’ve seen them. I’ve seen the catalogue from the Canberra gallery. I was very interested in the ones you call “Paranoic” where you cut the squares out of the steel engravings. You remember?

SN: yeah, yeah and it turns into a face. That is … owes some of it’s origin to Salvador Dali who had these paranoic images. You know, you turn to one side there are elephants, and the other side’s a snap (??) of a village. It just depends which way you look at it. That’s all the 30s, the prudent (??) 30s

MH: Was anyone else doing collage in Australia then?

SN: Yes, there was some guy. I’ve forgotten his name. He was quite good, but I no longer remember .. but he didn’t do collages actually in that sense, but he did objects, he collaged objects together. You know, toy tin rats and things together. I’ve forgotten his name .. he was in Melbourne.

MH: These have sat in a trunk in Sydney for 50 years

SN: It makes it very interesting for me because, you know, I’m seeing Mollison in May and these huge abstract things I’ve been doing which I’m perhaps going to make into collages, some of them, I think that’s the next series I do. And the words were in the poems, where are they, … there’s something about … Java …

MH: That’s it .. “the quartz of vision with the asphalt of human speech”

SN: yeah, “there have been interpolations, false syndromes like a rivet through the hand such deliberate suppressions of crisis as Footscray” … “upon the montage of the desecrate womb” .. you see, there it is there … this is the montage

MH: And Malley is a kind of collage because they glued bits of Shakespeare and everything together

SN: Yeah, “all must be synchronized, the jagged quartz of vision with the asphalt of human speech. Java”. So it all ties up with these

MH: And Ernst makes the point somewhere that collaboration is itself a kind of collage because you’ve got these two things

SN: Yes, well Breton had put that forward of course in a sense as the basis of surrealism.

So we’re all children of our times and it’s come round again – see there’s Mrs Fraser upside down, there’s Kelly hanged, there’s Moonboy. Ah, I haven’t seen this before. So I’m perhaps going to return to all that [pause] I think, after all this. It’s at a late age.

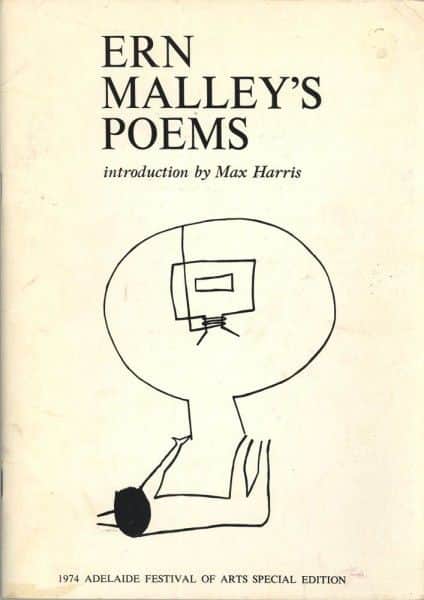

Sidney Nolan, cover for “Ern Malley’s Poems”, Mary Martin Publications, Adelaide, 1974.

MH: What was Harris like? I mean, you know it’s hard for me because I see what’s he’s like now, but what was he like then?

SN: Well he was very brilliant, sort of soft in a way, likeable.

MH: Good humoured?

SN: Yes, witty and debonair … he was very quick to discern what was happening abroad .. Henry Treece, Roskolenko, .. he was a very good editor.

MH: And he was a pretty talented poet

SN: He was a very good poet, he had a very good ear. You see actually he is the one who actually took the punishment of the whole thing.

MH: Yes, he copped it fair and square really. But I can see why that happened now, his poetry was not … was all tied up with his polemic about what Australia should produce and we should be doing that, whereas I can see for you that that side of it wasn’t there at all and that it was simply how the poems, Ern Malley connected with the sort of secret life that you had. So that’s why, I mean, then he had to take all the fallout directly, whereas

SN: Well I think he possibly blamed me a bit for being remote from the … In fact I know he did

MH: But what more could you have done?

SN: Well I was flat out living my own life. I couldn’t do any more and I was a painter, I was painting hard

MH: Well, and you were, technically at any rate, on the run from the law during that time

SN: Oh yes, I had every .. I had a double identity. My underpants had name tags on them which was ..

MH: Robin Murray

SN: Robin Murray. I had [unclear] papers. I had lots of things because if you were picked up the Military Police you’d get beaten up, you know, good and hard.

MH: Yes you’d go to jail

SN: You’d not only go to jail, they’d belt you, they’d knock you around .

MH: How did the name Robin Murray come about?

SN: I dunno, that was maybe Sunday’s idea … she always called me Robin, that’s Robin Red Breast. I think the Murray just arrived – I don’t know where from. But I had to go to films, openings of art exhibitions and all that, because I was very sophisticated. I knew all about the army, I knew all about the working class, I knew about the Military Police, my father had been one, and my father had told me what would happen to me; I’d go to jail and he wouldn’t come and get me out, and all sorts of things. So it was not altogether easy.

MH: No, I imagine it was very difficult. I’ve seen some of the letters that you had written to Sunday Reed when you were up in the Wimmera . Maybe you don’t want it to happen in your lifetime, but they should be published one day

SN: Well there are a whole lot of those. Yes, a great number of them.

MH: I’ve read them … just amazing. I was quite overwhelmed by them .. talking about painting, what you were seeing, and there were some bits to do with [unclear] … the Malley kind of thing

SN: yeah, well they were probably fairly cool aren’t they – but they’re probably not cool about painting are they – you see because they’d be read by a 3rd party, they’d be read by John, so I had to be careful about being too intimate, so I should think the letters are a lot about painting

MH: Yes, a lot about painting. They’re cool in one way, but they’re full of sadness in another, I mean that does come through, and loneliness. I mean it’s hard to talk about letters as though they were … but they’re remarkable things, quite quite.

SN: Yeah, well they probably should be published … She burnt all of her ones to me I believe when the guy was writing the book

MH: Haese?

SN: Haese… yes

MH: .. yeah, they’re not around ..

SN: .. she burnt ..

MH: he told me that too ..

SN: I had to ring her up … Mary wanted me to ring her up 20 years later. And I rang her up and um, it was a very difficult phone call. Apparently she went away and just burnt all her letters.

MH: Because she never forgave you for leaving?

[Long pause]

SN: No. … She could never see the logic of why I left. I couldn’t see the logic of – well I didn’t want to go either – but I couldn’t see the logic of staying … [pause] but she wanted it both ways you see, she wanted .. [pause] .. [unclear] and so did John … everyone wanted something that was impossible, which is natural for human beings ..[pause].. but they don’t usually get it. Except I’ve got it now. I think. I’d better go.

MH: I’m very grateful to you

[portion missing]

SN: … well they’re the love fruits … Douglas Cairns

MH: She says this is the Mitre Rock

SN: Yes it is, it’s the end .. Actually it’s the end of the Great Divide ..[long pause] see the likeness to “The Aunt’s Story”?

MH: Ah yes – this is the precursor of that ..

SN; yeah, that’s because of [unclear]

MH: and there’s the …

SN: yes, well they’re all going to America next year along with the Kellys, cause they’re very early abstracts [unclear] and from the point of view of American art that’s .. [unclear] .. that’s Ellsworth Kelly and so on

MH: Did you have the photograph in mind?

SN: No because I did another one despite the photograph

MH: But this wasn’t done

SN: No, that’s just completely abstract, that’s just … no, no, I didn’t have the photograph

MH: Because you can see the light and shade here ..

SN: Well I might have as a matter of fact now you come to mention it.

MH: It looks …

SN: yes

MH: There’s one .. of the collages

SN: You see I had them all worked out that when you looked that way and half closed your eyes you can pick up an image, and when you turn it that way you can pick up another image, and you can do it for the four corners.

MH: And what was it you were chopping up?

SN: They were , oh just a book of old master engravings, steel engravings. And I’m very much mixed up with that now. …[very long pause] … Well, they’re all dead, including the dog .. [pause] .. except for .. [pause] .. such a curious feeling isn’t it..

MH: Sinclair’s still alive

SN: No he’s dead

MH: Is he dead? When did he die?

SN: About three months ago .. [long pause]

MH: Must be a strange …

SN: Mmm, it’s a strange feeling .. [long pause] .. you see cause it’s the opposite of Patrick White in a way. You know I feel [pause] ..

MH: Tremendous affection.

SN: Yeah, I feel for all … yeah .. [long pause]

TAPE ENDS

END NOTES

- A view advanced by Nancy Underhill and with which I agree. See Underhill, Nolan on Nolan, Viking, Camberwell, Victoria, 2007, p. 7 and p. 231. ↩

- Papers of Michael Heyward, Australian Manuscripts Collection, State Library of Victoria, MS 13673, Box 5. Transcript by David Rainey, 2009.

- Alister Kershaw, see http://www.austlit.edu.au/austlit/page/OLD?id=A%5Br&idtype=oldid. In 1942 A Comment magazine published hoax poems written by Kershaw and Adrian Lawler in the fictitious names Mort Brandish and Rosa Lemmone.

- This refers to a postcard with the 1495 Dürer watercolour Trient which the hoaxers sent to Max Harris with the message “he did have a coloured postcard pinned up in his room which I haven’t included because the writing on the back seems to be personal.” The postcard rhyme is a slightly modified passage from Purcell’s opera Dido and Aeneas.

- These were published in Angry Penguins No 7.

- They refer to the poem Dürer, Innsbruck 1495 which was one of two or three sent by the hoaxers to Harris with their first letter.

- Alf Conlon headed the WW2 Directorate of Research and Civil Affairs based at Victoria Barracks in St Kilda Road, Melbourne where McAuley and Stewart allegedly wrote the Malley poems one Saturday afternoon in October 1943. See http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/conlon-alfred-austin-joseph-alf-9804. Conlan’s second-in-command was John Kerr, a young lawyer who 32 years later as Governor-General would dismiss Whitlam. An interesting account of the Directorate and the roles of Conlon and Kerr can be found in Richard Hall’s The Real John Kerr, Angus and Robertson, Sydney, 1978, p. 36 – p. 63.

One Comment

Join the conversation and post a comment.

this was very long Dad!